Returning Home: Deportations & Return Migration

While the number of people leaving Central America is well documented, less is known on how many return home, either voluntarily or involuntarily.

This article sets the record straight on some common myths and assumptions about migrants, remittances, and the industry.

It is often mentioned that remittances “are primarily spent on consumption, housing and land, and are not utilized for productive investment that would contribute to long-run development.”[2]

Statements such as these typically reflect value judgments rather than informed opinions based on empirical evidence. When they are broken down, they often fall into several assumptions: first, that remittances are kept separately from other sources of income; second, that consumption is inherently bad; and third, that investing remittances is the solution to the problem.

In the first case, some people have argued that remittances are kept apart from other sources of income, such as salaries, rents, or income from social programs. However, research by the Inter-American Dialogue and other institutions has clearly shown that this is not the case. Remittances are fungible[3] [4] and are mixed with other sources of income in the household. Moreover, data from Dialogue projects in 13 countries shows that remittances represent, on average, 37% of all income in the household.[5]

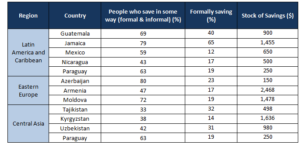

In the second case, there is a pervasive argument that spending remittances on “consumption” is inherently negative. However, Dialogue research shows that some of the top uses of remittances, regardless of the country, include food, rent, healthcare and education. It is difficult to argue that spending money on these priority areas is a “waste.” Finally, when remittance recipients are compared to non-recipients, in most cases, recipients as a percent of their cohort tend to save as much as non-recipients, if not more.[6] What these numbers suggest is that, first, expenses are not irrational, and second, that after expenses, remittance recipients manage to save.

In the third case, the argument that people should invest their remittances is problematic, not only because people are not misspending their income, but because investment is not the first step to achieve financial independence. The argument that productive investment will be best for long run development reflects a misconception about how financial independence is attained: not through productive investment, but by building wealth. Wealth accumulation results from disposable income, and savings generation is the first step. Having financial access to depository institutions is also important because it guarantees that savings will offer greater yields.

Investing in a business is not a guarantee that wealth will be accumulated, or that it will promote development; on the contrary, it may lead to greater losses. Promoting productive investments among people can yield the wrong output: certain markets may get saturated, informality may increase, and wages may even be driven down. More importantly, in any society the average person does not show entrepreneurial characteristics. It is inconsistent to expect remittance recipient households to behave differently from all other sectors of society, especially when what differentiates them is simply a family member working abroad, rather than entrepreneurial attributes.

“One of the more prohibitive elements of remittances, which adversely affects poorer users, is the high cost of sending money across borders,”[7] some writers have argued. According to a recent article by The Guardian, “a handful of firms are exerting a stranglehold over the global remittance industry by charging huge fees on money sent from friends and family abroad, choking an annual half a trillion dollar lifeline for countries that face sweeping economic challenges.”[8]

To address this claim, we break it down into its components: first, that the costs of remittances are prohibitive; second, that the remittance marketplace is uncompetitive; and third, that the savings from reducing transfer fees would have substantive development value.

First, though some claim that remittance costs are “prohibitive,” there is little indication that this is the case. Migrant remittances continue to grow, with the World Bank estimating 4% yearly growth for the period 2016-2017.[9] In this sense, costs of sending do not appear to be “prohibiting” sending. Moreover, migrants do not typically list price as their most important factor in choosing a remittance service provider (RSP): according to Dialogue surveys, top characteristics have included “ease of use” and “speed of service.” [10] A statistical analysis of migrant survey data, including amounts sent and fees paid, suggests that immigrants are relatively price-sensitive because they search for an affordable RSP but are prepared to pay more if the sending method is easier to use or more convenient. Specifically, those who think their RSP is inexpensive and transparent in its pricing pay up to 10% less, but those who say their RSP is easy to use pay up to 7% more for the service.[11]

Overall, the costs of sending money have dropped since 2000 when the debate over this issue started, though there are variations by country and by method of sending (cash, account, etc). Fifteen years later, the costs of sending money to Latin America and the Caribbean countries that comprise over 80% of flows has declined from roughly 10 to 5% on average.

Graphic 1: Pricing as % of Total Sent ($200), Comparison by Recipient Region

Source: World Bank Remittance Pricing Database, 3rd Quarter 2015.

While lower fees are a good thing for consumers, it is worth considering how the costs of sending money internationally stack up against other financial services. For example, given that the average ATM surcharge for out of network withdrawals within the United Sates $4.52,[12] paying $9.93 to send $200 to Mexico[13] does not seem exorbitant.

Second, the development of the money transfer industry over the past 15 years has been accompanied by waves of consolidation and significant competition. For example, surveys with migrants show that 36% of remittance senders shop around, using a variety of remittance companies depending on their needs (cost, location, convenience, etc.). Remittance agencies also report a high level of competition, with 70% of agents saying the market is more competitive now than it was in the past.[14] Moreover, companies have reported narrow profit margins along with increasing expensive banking service fees and risk management programs.[15]

Lastly, though reducing costs would put more money in migrants’ pockets, it would not necessarily have the major development impact that some claim it would. The World Bank’s 5X5 Plan, which aims to reduce the costs of remitting to 5% worldwide, would save an estimate $16 billion a year,[16] a significant amount of money. However, considering the sheer number of migrants worldwide, this comes down to just over $60 per migrant per year. Different strategies, such as helping migrants and recipients formalize their stocks of savings, would have a greater development impact, according to Dialogue research (see Myth #6).

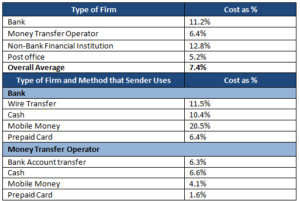

It is often incorrectly assumed that sending money through banks is inherently cheaper.

According to pricing data from the World Bank, on average it is more expensive to send with banks than with remittance companies. This is largely due to the fact that most banks offer only wire transfer services,[17] which tend to be very expensive and are often better suited for large, business transactions than for small-scale family remittances. In fact, the average cost of an outgoing international wire transfer is $47.50,[18] making wire transfer a very poor choice if you are sending a family remittance transfer of, say, $250.

Money transfer operators, on the other hand, generally offer specially designed remittance services that are intended for customers sending small, frequent amounts of funds to family overseas. As the table below shows, these products tend to be more economical.

Table 1: Costs of Sending $200, Selected Types of Firms and Products (%)

Source: World Bank Pricing Database, Second Quarter 2016.

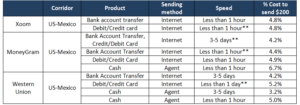

What is interesting to note is that, when using a remittance service, there are some savings associated with connecting that service to a bank account. As the table below shows, there are a wide variety of ways to send money and receive money, each with slightly different costs. Migrants choosing between these options may consider speed, convenience, cost, reliability, customer service, and payout options for the recipient. As the table below indicates, some of the cheapest services include those that are slower and those that are connected to bank accounts.

Table 2: Costs of Sending $200, Selected Types of Firms and Products (%)

Source: World Bank Pricing Database, Second Quarter 2016.

** Please note that pricing database was not accurate and was updated by authors on 10/3.

Remittance agents and companies rely on bank accounts to store, move, and pay out funds. Unfortunately, recent years have given rise to the myth that remittance companies are simply “too risky” to bank.

Since the early 2000s, the bank accounts of remittance companies have been subject to significant regulatory scrutiny from a wide range of public agencies and banking institutions. As a consequence, these accounts, which serve as vehicles for third-party cash transfers, are often identified and suspected of financial threats such as money laundering. Within the context of remittance transfer intermediation, remittance companies need access to bank accounts in order to perform essential back-end operations. Holding a bank account allows an RSP to receive deposits from its agents as well as to deposit funds for payers.

Regulators expect robust risk management mechanisms from remittance companies, including various reporting obligations of suspicious activities, in order to safeguard their activities and maintain bank accounts. However, remittance companies and their agents have been subject to an increased and somewhat systematic practice of account closures both on the assumption of risk and as a measure of risk prevention.

The practice of closing accounts is occurring in the United States, but is not limited to the US context. A recent study by The World Bank Group surveyed 13 governments, 25 banks and 82 remittance companies in countries around the world. Among its findings, 46% of remittance companies have received notifications from their banks regarding the upcoming closures of their accounts. Of the 25 banks, 5 indicated they do not offer services to remittance companies, and 15 indicated they do not open accounts for agents of remittance companies.[20]

However, the reality is that remittances represent a low risk for money laundering or terrorism financing, and that most companies already have robust risk management practices in place. To begin with, remittance companies manage risk with their existing prevention mechanisms and are in line with US government regulations.[21] Remittance companies also undergo regular audits and are supervised by entities at the state, federal and international levels.

Moreover, most remittances are small-value transfers of approximately $300, which simply does not fit the profile of large-scale money laundering.

In fact, Dialogue research has shown that while there is a strong correlation between Anti-Money Laundering risk[22] and fragile states,[23] the same is not the case with Anti-Money Laundering risk and remittance recipient countries. The following graphics demonstrate this point.

Graphic 2: BASEL Risk Scores and State Fragility

Source: Data compiled by the author based on various sources, including the Index on State Fragility, the World Bank data on remittances and the Basel AML risk index.

Graphic 3: BASEL Index and Remittances as Share of GDP

Source: Data compiled by the author based on various sources, including the Index on State Fragility, the World Bank data on remittances and the Basel AML risk index.

Donald Trump received a great deal of publicity for recent comments suggesting that the United States should cut off remittances to Mexico, which he said were “de facto welfare for poor families in Mexico.”[24] However, Trump was not the first, nor will he be the last, to make this argument. For example, a 2015 article by the Financial Times explained that remittances are “effectively foreign aid organised by private citizens.”[25] Even The Guardian has written that remittances are now “more than three times larger than total global aid budgets, sparking serious debate as to whether migration and the money it generates is a realistic alternative to just doling out aid.”[26]

There are several issues with this claim. To start with, remittances are private, family to family funds. Migrants do not intend remittances to serve as development aid for an entire country, but rather, to support key family members and loved ones on a personal level. In many cases, the sender and the recipient are members of a nuclear family, despite the transnational nature of that family. The remittance is family money, and neither sending nor receiving government can mandate how it is spent.

The second issue with this claim is that the term “aid” or “welfare” suggests a handout, whereas the data show that many recipient families are also working, and that remittances, on average, constitute only 37% of recipient household income (See Myth # 1).

Third, even in countries that are highly dependent on remittances, the majority of the population does not receive remittances. Even in Tajikistan, the most remittance dependent country in the world, only one in three households has had a family member working overseas.[27] It is also important to note that though most recipient families are not wealthy, they are also not the poorest of the poor. Due to the high costs of international migration, typically the poorest households do not migrate internationally and are not able to send cross-border remittances. In this sense, remittances could be considered an inadequate substitute for government assistance since they do not reach everyone, and do not reach the poorest of the poor.

Lastly, if indeed remittances were to replace development aid, they would constitute a very regressive form of aid. Many migrants work long hours in difficult and dangerous conditions, and endure a great deal of suffering to be able to send money home. While they might be able to improve the living situation of their immediate family back home, to place the responsibility and the burden for development aid on their backs seems hardly fair.

Remittances are often equated with development, or presented as a sort of panacea for development problems. In reality, however, the relationship between remittances and development is complex, multidirectional, and highly influenced by policy environments.

Many households rely on remittances, along with a variety of other sources of income, to help cover expenses related to food, housing, education, and health. That remittances enable them to cover these important areas and improve living standards is no doubt positive. However, it is also important to consider how remittances can be leveraged to build prosperity, rather than simply sustain survival. Aside from temporarily improving quality of living, how can remittances promote development?

The answer lies in the relationship between remittances and savings. Out of all income earned, remittances included, savings are set aside and built. Because remittances have the effect of increasing disposable income, they also increase the household’s capacity to save. Thus, at the level of the household, remittances fulfill the function of contributing to build liquid and fixed assets.[28]

From here, much of the development impact of remittances depends on access to financial services, such as bank accounts. Unfortunately, many remittance recipients may come in to a banking institution to pick up their remittance without realizing that they can use financial services, such as savings accounts, insurance and even credit to build and protect their assets. In many cases, the savings generated by remittances are kept informally, “under the mattress,” as the following table shows.

Table 3: Savings capacity of remittance recipients

Source: Data from financial education programs in various countries.

In this sense, financial access can substantially expand the development impact of the remittance transfer. On a household level, formal savings ensures that a family’s stock of savings remains secure; it is safeguarded from natural disasters, crime, or other unexpected events. The benefits of formal savings also include earning interest and gaining access to other financial services (i.e., with a savings account, the client may be able to apply for a credit card, and with that credit card build a credit history that will eventually enable them to receive a home loan).

Savings at an aggregate level strengthen financial institutions and may ultimately ease access to credit for investment.

In light of these dynamics, it is important to highlight that remittances do not “create” development automatically. Rather, it is more accurate to say that remittances have important economic impacts that can be leveraged for development through good policies.

There is a tendency to overestimate the degree of informality in the remittance market, thereby portraying migrant remittances as informal, unregistered, and unregulated. For example, researchers have argued that there is “a whole range of formal and informal channels for remitting, chosen on the basis of cost, reliability, accessibility and trust. As a result, a large share of remittances is through informal channels and thus remains unrecorded.”[29]

While informality does exist, particularly in certain corridors, the vast majority of remittances move through formal and regulated channels, particularly in the period since 9/11. For example, in the case of the Philippines, the country’s bank estimates that by 2007, 95% of remittances were recorded by the banking system, compared to only 72% in 2001.[30] With regards to migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean, 95% of remittances are sent by formal means, up from 88% in 2010.[31]

Even among countries that have experienced higher levels of financial informality, levels are rapidly decreasing. In the case of Bangladesh, a 2010 study found that 17-24% of remittances were informal, down from 54-60% five years ago.[32] Even in Somalia, one of the most informal countries in the world, 73% of remittances are received through formal payment methods, according to surveys of recipient households.[33]

Likewise, there is a myth that non-bank remittances are, by very definition, informal. In fact, remittance companies and their local agencies are highly regulated at the state, national and international levels and remittances sent via remittance agencies are considered formal remittances (see Myth #4).

In recent discussions, mobile transfers have been hailed as a “gamechanger.”[34] “Mobile Money Set to Disrupt International Remittances Market,” reads one headline.[35] Some people have claimed that “mobile phones have evolved in a few short years to become tools of economic empowerment for the world’s poorest people.”[36]

The reality is a little more complex. While mobile transfers are exciting in terms of their potential, current usage should not be exaggerated. Worldwide, only 16% of the population has used a mobile phone to make a transaction from their bank account, and only 2% of the population has a mobile money account.[37] Even among those who use mobile phones to send and receive money, the “grand majority” of these mobile transactions occur at the domestic, rather than the international, level.[38] Finally, the number of mobile accounts may not be an accurate representation of their actual levels of use. Among those with mobile accounts, only 35% are active users, that is to say, they have used their account in the past three months.[39] Meanwhile, though mobile does offer important inclusion opportunities for traditionally underserved groups, most studies indicate that mobile money customers today are mainly urban, male users – the “typical early adopters.”[40]

Mobile remittances face a number of challenges, including regulatory, security and legislative hurdles. As IFAD notes, policy challenges are particularly great for cross-border mobile transfers, which may be the reason that “international services have been rather stagnant when compared to domestic mobile transfers.”[41]

This is not to say that mobile remittances don’t hold great potential. On the contrary, their potential impact is tremendous, and it will be exciting to see the trajectory they take. But it’s important not to overstate their current reach in our optimism for their potential.

Bitcoin proponents have argued that Bitcoin is a “sought-after currency among the people,” especially for its “low value payments since there isn’t a fixed minimum fee which gets charged to send money for a transaction either to the person sitting next to them, or to a business or a peer-to-peer on the other side of the world.”[42]

There are several issues with this claim. First of all, as noted in a recent article in The Atlantic, the use of Bitcoin does not inherently reduce costs: “the price of transacting over Bitcoin depends on how much demand there is to use the network at a given time.” If the number of transactions continues to increase, without improvements in the processing capacity of the network, we could see increased costs as well as delays in sending.[43] Currently, a bitcoin transaction occurs by mining new bitcoins, which are produced in blocks. These blocks are used to record all transactions made via bitcoin, and have a maximum size of 1 MB, meaning they can only record seven transactions per second, maximum. As the International Business Times notes, “to put this in context, Visa says its payment system processes 2,000 transactions per second on average and can handle up to 56,000 transactions per second if needed.”[44]

Second, Bitcoin exchanges as well as individual users may have trouble finding or maintaining banking services, a struggle which is well understood by the remittance industry. In the absence of clear legislation, “those buying and selling Bitcoin will continue to struggle with old-school institutions and their conservative approaches to cryptocurrencies. Unfortunately, Bitcoin has to rely on these very institutions for legitimacy, integration, and, ultimately, more widespread adoption.”[45]

Thirdly, and most importantly, there is an issue with the user profile. Many migrants who send remittances are working long hours to support family back home, with little time or inclination to research cutting edge fin-tech products. Indeed, even in the case of the much-lauded “BitPesa” in Kenya, most international transfers are business transfers, rather than individual transfers. Within the limited sphere of individual transfers, the founder of BitPesa estimates that most are in fact “self transfers” between two bank accounts owned by the same person. The average user is “a far cry from the poor, rural farmer so often celebrated in the story of Bitcoin and low-value remittances.”[46]

Given these dynamics, it would be a mistake to overstate the current use of Bitcoin for family remittances. In the future, Bitcoin will have to address a number of challenges and hurdles before it can be considered a viable alternative to existing methods of sending.

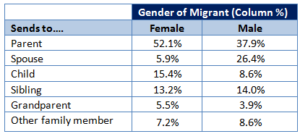

As Jesus Cervantes of CEMLA writes, “it is commonly though that remittance flows (…) stem from a migratory process where men leave their country to seek better employment and income opportunities, and then send remittances to their wives and children back home.”[47]

The reality is a little more complex. Not only are women increasingly migrating themselves, but the relationships between remittance senders and recipients are diverse and expansive, reflecting the transnational nature of many families.

A wide variety of studies have shown that, in countries around the world, the recipients of remittances do tend to be women. In Guatemala, for example, 63% of primary remittance recipients are women. In Colombia, 70% of remittance recipients are women. A study of BANORTE transfers to Mexico found that women receive 72% of all remittances to that country.[48]

Though many women are remittance recipients, they are not limited to this role. In fact, today women account for nearly half of all international migrants,[49] and many women send remittances to family back home. In most cases, remittances sent by female migrants are smaller in amount than those sent by male migrants, but similar as a percentage of salary, since female migrants tend to earn less money.[50]

A recent Dialogue study found that women are responsible for much of the increase in remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean in the post-recession period. While male migrants reported sending remittances of nearly the same amount and frequency from 2009 to 2014, female migrants reported spending more money and more frequently.[51]

Finally, migrants send to a variety of family members back home, and not just their wife or their husband. As the table below indicates, 52% of female migrants and 38% of male migrants send money to their parents. Many male and female migrants also send remittances to children in their home country, reflecting the transnational nature of many migrant families.[52]

Table 4: Primary Recipient of Remittance, According to Migrant

Source: Survey of 2000 Latin American and Caribbean Migrants in the United States, Inter-American Dialogue, 2014.

[1] For more on this topic, see Orozco, “On the ‘Productive’ Use of Remittances and their Significance for Asset Building,” Inter-American Dialogue, February 2015. Full article available at goo.gl/IaxfEK

[2] See for example, Pant, “Harnessing Remittances for Productive Use in Nepal,” Economics Review at Nepal Rastra Bank, 2011. Available at goo.gl/VBwjwq. See also “Remittance Debate Revisited: New Evidence from Indian Migrant Labor in Lebanon, available at goo.gl/A1mKVP.

[3] Zarate Hoyos, New Perspectives on Remittances from Mexicans and Central Americans in the United States, Kassell University Press, 2007, see chapter 2.

[4] Adams, Cuecuecha, and Page, “Remittances, Consumption and Investment in Ghana,” World Bank Working Paper, 2008.

[5] Data from financial education programs in various countries performed by Manuel Orozco with the Inter-American Dialogue and Developing Market Associates. Sample size 93,000 clients.

[6] For example, in the case of Jamaica 77% of non-recipients report saving in some way (formal and informal), compared to 79% of remittance recipients. In Mexico, 56% of non-recipients report saving in some way, compared to 59% of remittance recipients. Data from financial education programs in various countries performed by Manuel Orozco with the Inter-American Dialogue and Developing Market Associates.

[7] See Milanovic, “Developing a Global Financial Architecture,” TechCrunch, 20 August 2016. Available at goo.gl/Q8KT3U

[8] Anderson, “Global Remittance Industry Choking Billions out of Developing World,” The Guardian, 18 August 2014. Full article available at goo.gl/UPcixQ

[9] “Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook,” KNOMAD and The World Bank Group, April 2016. Available at goo.gl/ytTMUZ

[10] Results based on a survey of 2,000 migrants by the Inter-American Dialogue in 2014 and a survey of 200 migrants by the Inter-American Dialogue in 2015.

[11] See Orozco, Porras and Yansura, “The Costs of Sending Money to Latin America and the Caribbean,” Inter-American Dialogue, February 2016.

[12] Bell, “Another Record-Setting Year for Checking Account Fees,” Bankrate, 5 October 2015. Full article at goo.gl/pqrZ34

[13] World Bank Pricing Data for US-Mexico Corridor, Collected May 11 2016. For more information, see https://remittanceprices.worldbank.org

[14] Surveys with remittance agencies, Inter-American Dialogue, 2013.

[15] See Orozco, Porras and Yansura, “Bank Account Closures: Current Trends and Implications for Family Remittances,” Inter-American Dialogue, December 2015.

[16] Nicoli, “5×5 = US$16 billion in the pockets of migrants sending money home,” World Bank Blogs, 27 November 2012. See goo.gl/fyhtJq

[17] One important exception to this is Wells Fargo, which offers a special remittance product called ExpressSend. For more detail, see goo.gl/IK0H6h

[18] Kim, “Comparing Wire Transfer Fees at the Top 10 U.S. Banks,” My Bank Tracker, 6 May 2016. Full article at goo.gl/m8sVX7

[19] For more detail, see Orozco, Porras and Yansura, “Bank Account Closures: Current Trends and Implications for Family Remittances,” Inter-American Dialogue, December 2015.

[20] See “World Bank Group Surveys Probe “De-Risking” Practices,” World Bank Publications. Available at goo.gl/7Sen2D

[21] See for example, National Terrorist Financing Risk Assessment 2015, US Department of Treasury, p.53.

[22] As measured through the Basel AML Index, an annual ranking assessing country risk regarding money laundering/terrorism financing. It focuses on anti-money laundering and counter terrorist financing (AML/CTF) frameworks and other related factors such as financial/public transparency and judicial strength. For more, see https://index.baselgovernance.org/

[23] As measured by the Fragile States Index of the Fund for Peace. For more, see https://library.fundforpeace.org/fsi

[24] “Memo explains how Donald Trump plans to pay for border wall,” The Washington Post. Available at goo.gl/GrxAOO

[25] Klein, “What might Trump’s Remittance Plan do to the Trade Balance?” Financial Times, 13 April 2016.Available at goo.gl/v4FuZB

[26] Provost, “Migrants’ Billions Put Aid in the Shade,” The Guardian, 30 January 2013. Available at goo.gl/rWVG5u

[27] Danzer, Dietz and Gatskova, “Tajikistan Household Panel Survey: Migration, Remittances and the Labor Market,” IOS, 2013. For full report, see goo.gl/28M390

[28] For a more detailed discussion, see Orozco, “Remittances and Assets: conceptual, empirical and policy

considerations and tools,” UNCTAD, 2012. Available at goo.gl/Bhz2av

[29] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Report, “Economic Development in Africa,” 2016. Available at goo.gl/G4s6IW. Quoted in The Guardian at goo.gl/xzDBi7

[30] See Amjad, Irfan and Arif, “How to Increase Formal Inflows of Remittances,” IGC Working Paper, May 2013. Available at goo.gl/pkSijh

[31] Orozco with Jewers, “Economic Status and Remittance Behavior Among Latin American and Caribbean Migrants in the Post-Recession Period,” Inter-American Development Bank, 2014.

[32] See Amjad, Irfan and Arif, “How to Increase Formal Inflows of Remittances,” IGC Working Paper, May 2013. Available at goo.gl/pkSijh

[33] Orozco and Yansura, “Keeping the Lifeline Open: Remittances and Markets in Somalia,” Oxfam, 2014. Available at goo.gl/fosYkE

[34] See, for example, Murphy, “Sending Cash Home: Mobile Money is a Gamechanger,” The Guardian, 29 September 2015. Available at goo.gl/zOW1VY

[35] “New Consumer Research: Mobile Money Set to Disrupt International Remittances Market,” Global News Wire, 21 January 2016. Available at goo.gl/Xauari

[36] “The Power of Mobile Money,” The Economist, 24 September 2009. Available at goo.gl/zgKH4r

[37] Global Findex, World Bank, 2014 (most recent year available for this question).

[38] “Remittances and Mobile Banking,” Financing Facility for Remittances, IFAD. See goo.gl/FoJRSv

[39] “2014 State of the Industry: Mobile Financial Services for the Unbanked,” GSMA, 2014. Full report at goo.gl/9XVdpK

[40] “2014 State of the Industry: Mobile Financial Services for the Unbanked,” GSMA, 2014. Full report at goo.gl/9XVdpK

[41] “Remittances and Mobile Banking,” Financing Facility for Remittances, IFAD. See goo.gl/FoJRSv

[42] Ogundeji, “From Remittance to Startups, How Bitcoin is Used in Africa,” 30 April 2016. Available at goo.gl/oc89ac

[43] For more detail, see Barabas and Zuckerman, “Can Bitcoin Be Used for Good?” The Atlantic, 7 April 2016. Available at goo.gl/mLpwZn

[44] Gilbert, “Bitcoin’s Big Problem: Transaction Delays Renew Blockchain Debate,” International Business Times, 4 March 2016. For full article see goo.gl/Qcx5tN

[45] Razavi, The Struggle Between Bitcoin Traders and British Banks,” Vice, 13 January 2015. Available at goo.gl/MPLZqz

[46] For more detail, see Barabas and Zuckerman, “Can Bitcoin Be Used for Good?” The Atlantic, 7 April 2016. Available at goo.gl/mLpwZn

[47] Cervantes, “Female Migration and Remittance Flows to Mexico,” CEMLA, 2015. Available at https://www.cemla-remesas.org/principios/pdf/201501-FemaleMigration.pdf

[48] Monroy and Cervantes, “Women Move: Mexican Women and Remittances,” People Move Blog, The World Bank, 5 May 2015. Available at https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/women-move-mexican-women-and-remittances

[49] Monroy and Cervantes, “Women Move: Mexican Women and Remittances,” People Move Blog, The World Bank, 5 May 2015. Available at https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/women-move-mexican-women-and-remittances

[50] Monroy and Cervantes, “Women Move: Mexican Women and Remittances,” People Move Blog, The World Bank, 5 May 2015. Available at https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/women-move-mexican-women-and-remittances

[51] Orozco with Jewers, “Economic Status and Remittance Behavior Among Latin American and Caribbean Migrants in the Post-Recession Period,” Inter-American Development Bank, 2014.

[52] According to this same survey, 35.3% of Latin American and Caribbean migrants have children living with them in the United States, 28.2% have children living in their home country, and 9% have children in both countries. Twenty seven and a half percent do not have children at all.

While the number of people leaving Central America is well documented, less is known on how many return home, either voluntarily or involuntarily.

Public policies related to migration and development in Central America are relatively recent, limited, and diffuse.

The Pope’s five-day trip across Mexico is on a route deliberately made to draw attention to the dangerous journey taken by migrants to the US.