Chinese Reactions to the Brazil Protests

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

This post is also available in: Spanish

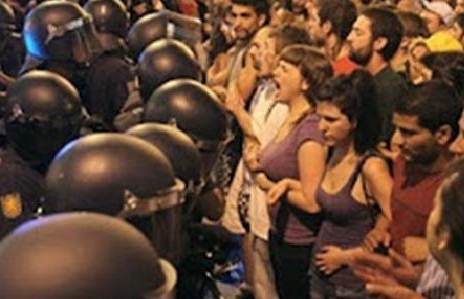

During my first week as a Program Assistant for Education at the Inter-American Dialogue, I had the privilege to help organize and attend an event about the recent education policy proposals in Chile. This is truly a hot topic at the moment. Since 2011 Chile has been rocked by powerful student protests that call for free higher education for all, an end to for-profit schools, and greater education quality and equity, among other requests. In response to the protests, President Michelle Bachelet submitted a proposal to Congress in May hailed as “Chile’s most significant education reform in 50 years.”

It is refreshing to see that at least some governments in Latin America are responding to the demands of their citizens. In Venezuela, where I come from, it is a whole different story. Earlier this year, the Minister of Education, Hector Rodriguez, made the following remark: “…It’s not like we (the government) are going to take people out of poverty so they become middle class and turn into escuálidos (term used by chavistas to refer to opposition supporters).” In other words, the government does not want to educate the people for fear that they will turn against the so-called socialist revolution.

President Bachelet’s proposed reform would bar schools from charging copayments above and beyond the public funding they receive, require for-profit schools that receive public funding to become non-profit, and prohibit primary schools and kindergartens that receive public funding from picking and choosing their students. These are only a few proposals on a very ambitious reform.

Dialogue Senior Fellow Sergio Bitar, a former Chilean senator and minister in three administrations, started the discussion by analyzing the reforms and assessing their relevance for other Latin American education systems. According to Bitar, the three main objectives on education in Chile are: “increase efforts to improve quality for all, expand access of lower-income groups, and reduce segmentation and gaps in quality.” In his view, Bachelet’s reform does not respond to these objectives in the most direct and effective way, but a thorough review of the proposals would help obtain more realistic results.

Bitar argued that the main challenges of the reform will be “how to achieve the change from for-profit to non-profit schools, together with eliminating copayments.” These changes can have serious political implications. For example, the owners of for-profit schools will go to the parents and say ‘now you only have two options: you can switch your child to a public school, or you have to pay full tuition.’ Scenarios like this one can become a major problem in Chile, which, despite the protests, is home to one of the highest-quality education systems in Latin America.

Emiliana Vegas, chief of the Education Division at the Inter-American Development Bank, followed with some critical remarks about the state of education in Chile. “Something that has really struck me and my team is that the rules are very different for public and private schools,” she said. This situation makes for “a market that is not truly competitive because different providers have different conditions to operate.” Vegas agreed with Bitar in that the system is not providing quality for all.

However, Vegas took the time to recognize the progress in the Chilean education system. She highlighted three major accomplishments: first, today in Chile most children can expect to finish 12 years of education, which is very unusual in Latin American countries; second, Chile has the highest PISA scores in the region; and third, the gap between students who come from poor and rich households has decreased.

Sergio Urzua, Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Maryland, adopted perhaps the most critical stance in the discussion. “What word would I use to describe these education reforms? It’s actually improvisation,” he said. In his view, all the titles are great, but the subtitles and especially the footnotes of the reform are alarming. According to Urzua, the proposals are not tackling the three main challenges of education in Chile: “better teachers for more vulnerable students; better teachers for more vulnerable students; and better teachers for more vulnerable students. Period.”

Bachelet’s education reforms have generated a lot of controversy, with some saying they go too far, and others arguing they don’t go far enough. Bitar is confident that the reforms will eventually be approved since there is a majority in both Congress and House to move forward with the process. In his view, however, the reforms need to be adjusted. They need to improve communication with parents; they need to review the sequence of implementation of the reforms; and they need to prepare a better long-term plan in order to achieve the desired results.

I am very curious to see what will happen with education in Chile in the next few years. Is Chilean society ready for these radical changes? Only time will tell. From my perspective, it is truly admirable that even though Chile has improved its education system significantly in the last decade, their success has pushed its citizens to demand even better policies and results.

Protests in Brazil are currently the focus of discussion and debate within Chinese government institutions.

Unique lens into what those who know education policy best are saying about current trends in Latin America.

Protests in Chile are a consequence of social successes and failures in the country.