Latin America Advisor

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

What Must Be Done to Stop the Spread of Zika?

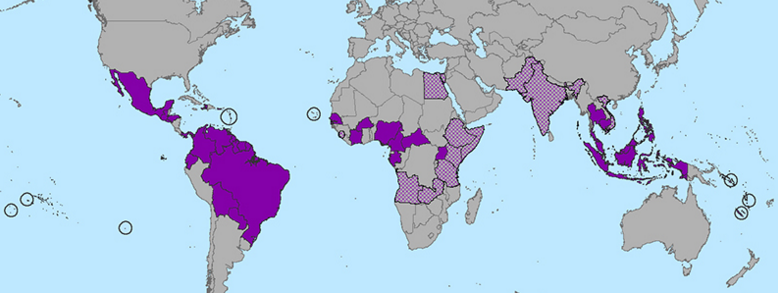

The mosquito-borne illnesses Zika has continued to spread in Brazil as the country prepares to host the 2016 Olympics in August. Reported cases of the Zika virus, which health experts believe is linked to microcephaly, or the condition in which infants are born with undersized skulls and brains, have continued to rise, with 199 new cases reported for the week ending on Jan. 2. The number of Zika-related microcephaly cases in Brazil recently surpassed 3,000, and Brazil’s Health Ministry has declared the virus’ spread to be a national emergency. Locally acquired cases of the virus have also been reported in other locations in the Western Hemisphere, including Mexico, Central America and other parts of South America. Are public health authorities coordinating an adequate response to fight the disease? What additional steps must authorities take to prevent the disease’s spread? Will Zika become a public health crisis for other countries in the Western Hemisphere as it has in Brazil?

Joaquin Molina, representative of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in Brazil: “Since Brazil detected its first locally acquired cases of Zika infection last May, 19 other countries and territories of the Americas have reported local transmission of the virus: Bolivia, Barbados, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guyana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Puerto Rico, Paraguay, Saint Martin, Suriname and Venezuela. Like chikungunya before it, Zika has spread rapidly in the region because the entire population lacks immunity to the virus and because Aedes, the mosquito that transmits it, is widely distributed. Most people who become infected with Zika do not develop symptoms, but there is growing evidence linking Zika infections during pregnancy with microcephaly, or smaller-than-expected head size, in newborns. Brazil has reported more than 3,500 suspected cases of microcephaly in areas where Zika is circulating. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) is coordinating with Brazilian officials and other partners, including Brazil’s Fiocruz, the Pasteur Institute and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control to investigate this relationship and other aspects of Zika. PAHO is also providing technical cooperation in areas including case definition of microcephaly, analytical methodologies, laboratory diagnosis, integrated surveillance of arboviruses (dengue, chikungunya and Zika), and monitoring and tracking of cases. To help other countries prepare for and respond to Zika, PAHO is helping ministries of health improve laboratory capacity to detect the virus, providing recommendations for clinical care and follow-up of infected patients (in collaboration with national professional associations and experts), and encouraging monitoring and reporting on the virus’ spread and the emergence of complications. PAHO considers the best prevention to be to continue efforts to control Aedes mosquitoes, which in addition to Zika, also transmit dengue and chikungunya. In this sense, Zika is an opportunity to step up investment and action for mosquito control to fight all three of these related viruses at the same time."

Katherine E. Bliss, senior associate of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS): “Zika virus was first identified in monkeys in Uganda’s Zika Forest in 1947 and was then isolated in humans. Like the dengue and chikungunya viruses, it is transmitted to people by mosquitoes of the Aedes genus. Zika, which can cause fever, headache and rash, is considered to be endemic in parts of Africa and Asia, but it had not been reported in the Americas until 2014, when authorities on Easter Island detected Zika there, following an outbreak in French Polynesia. With Aedes mosquitoes present in most countries in the region, 17 have now reported local transmission of Zika. Since May, there have been an estimated 440,000 to 1,300,000 cases reported in Brazil, with most concentrated in the Northeast. Particularly worrisome to officials is the apparent association between a pregnant woman’s infection with Zika and fetal microcephaly; according to reports, the number of infants born with smaller-than-average heads was 20 times higher in 2015 than in 2014. The anticipated arrival of thousands of tourists in Rio de Janeiro for the Olympics in August also raises concerns, and Brazilian health authorities are working now with community and education officials in neighborhoods bordering the Olympic area in Rio to control mosquito populations, raise popular awareness of Zika symptoms and urge pregnant women to seek prenatal care. PAHO has also deployed experts to help member states strengthen surveillance measures for Zika virus, improve laboratory and detection capabilities, and map the virus’s spread.”

Meredith Fensom, consultant at the World Bank and policy advisor at the Americas Health Foundation: “The Zika virus continues to spread, and current technology offers no clear way of stopping the virus. Brazilian authorities are committed to fighting the disease, but success has been limited. Zika, along with dengue fever and chikungunya, is spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. The Zika virus was likely brought to Brazil during the 2014 World Cup. Officials estimate between 440,000 and 1.3 million people there are infected. In 2015, the Brazilian Ministry of Health established a relationship between microcephaly and Zika virus, declaring a national emergency after more than 2,400 babies were born with microcephaly. In 2014, there were 147 cases. Most babies born with microcephaly die young, and many survivors have life-long cognitive impairment. There is no cure. Brazilian authorities have urged women in certain regions to avoid getting pregnant. Additional research must be undertaken to understand the connection between Zika and microcephaly. Current mosquito control and education programs have been minimally effective, and there is no vaccine. One potential solution is offered by Oxitec’s genetically engineered mosquitoes, which have been more than 90 percent effective at reducing local populations. The genetically engineered mosquitoes have not been put into practice on a large scale, but are among the more compelling approaches to combating the spread of this disease. Zika is spreading rapidly, and the Western Hemisphere is at risk. The latest Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) data confirms cases of Zika virus in 14 regional countries and territories. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently confirmed Zika in a traveler from Texas and predicts outbreaks will come to Florida, Gulf Coast states and maybe Hawaii.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue's Corporate Program and others by subscription.