Official: Funding Issues Critical to US Security Programs

Focusing on transnational crime is a top priority of the Obama administration’s policy in Latin America.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Mexico just celebrated the 17th anniversary of its accession to the OECD and, earlier, the ratification of NAFTA. During this period, Mexico has made significant progress in many areas, notably its remarkable macroeconomic management and continued improvements in addressing inequality.

Still, the question remains if Mexico has achieved a degree of institutional development consistent with its participation in those organizations. Simply stated, the answer is no. It remains far behind its partners in NAFTA, the United States and Canada, and it is a laggard among the members of the OECD. I recently attended a Ditchley Foundation-sponsored conference in England on the future prospects of Mexico, where the consensus was that Mexico has made progress in many areas, but it's running the risk of falling behind other emerging economies.

Mexico's indicators in key indices further demonstrate its relative shortcomings. While performing well overall, in selected indices Mexico faces challenges in terms of law compliance, contract protection bankruptcy (closing a business) and property rights-all in the world's lower half, as shown in the table below.

A clear illustration of this problem has occurred recently regarding the bankruptcy of Vitro, giving rise to potential concerns about Mexico's institutional maturity. Vitro-a large industrial conglomerate with a considerable number of subsidiaries-had been involved in risky derivative contracts during the 2008 crisis. Its current bankruptcy case-indeed locally the most high-profile case since Mexico's bankruptcy reform-is now underway and will offer insights into how Mexico will treat bankruptcy law going forward. Because of these transactions and other financial problems, Vitro defaulted on $1.7 billion in 2009 and requested bankruptcy protection. Even though Mexico has a new bankruptcy law, the Vitro case poses a test for the Mexican bankruptcy process' treatment of defaulting corporations. In the course of the case, Vitro is seeking to have its subsidiaries vote as creditors of the company, thereby diluting the voting power of bona fide outside creditors. Specifically, Vitro has made numerous intra-company loans to its subsidiaries, totaling $1.9 billion, and is seeking to count these loans in the bankruptcy process. This practice-wherein subsidiaries of the company vote on their own bankruptcy-puts legitimate creditors at a disadvantage.

If the courts are to accept this position, it would be a blow to Mexico's image as protecting the interests of investors and would have large implications for Mexican corporations looking to borrow funds from

abroad. In this regard, Mexican jurisprudence should emulate the well-established U.S. corporatebankruptcy code, which does not allow defaulting companies' subsidiaries to vote in their own bankruptcy by creating fictitious intra-company loans. There would be setbacks for Mexico as an attractive foreign investment destination if it does not take steps now to stabilize and improve its bankruptcy code, which is potentially susceptible to cronyism.

Focusing on transnational crime is a top priority of the Obama administration’s policy in Latin America.

Despite reports in recent months that Mexican manufacturing is experiencing a resurgence, Mexico’s industrial sector faces tremendous challenges.

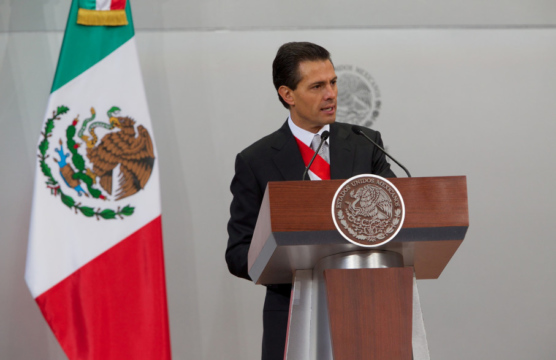

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto marks 100 days in office. Is he focusing the beginning of his presidency on the right goals?