Impact of Lower Commodity Prices on Latin American Growth

With the recent decline in commodity prices, why have some countries have fared better than others?

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra appointed new ministers this month as dismissed lawmakers’ challenges to his presidency died down. The new cabinet’s swearing-in followed the president’s invocation of the Constitution to dissolve Congress and call for new legislative elections, an act that triggered a standoff with opposition legislators and ultimately resulted in Vice President Mercedes Aráoz’s resignation. Was Vizcarra’s move justified? What consequences does Congress’ dissolution have on Peruvian politics in the short and long terms? Is the president now more emboldened than ever, and will he finally be able to pass his controversial anti-corruption reforms?

Cynthia McClintock, professor of political science and international affairs at The George Washington University: “Vizcarra’s approval rating has soared toward 80 percent. Most Peruvians despised a Congress that had brazenly flouted Vizcarra’s anti-corruption reforms and archived his proposal for early legislative and presidential elections. On Sept. 30, Vizcarra tied a vote of no confidence to transparency in the Congress’ election of new members of Peru’s Constitutional Tribunal, stipulated to be ‘autonomous’ in Peru’s constitution. (The tribunal was to rule on the pre-trial detention of Keiko Fujimori, the leader of the dominant party in Peru’s legislature, accused of corruption.) Aware that a vote of no confidence would spark its dissolution, the Congress did not so vote, but it elected a new member for the tribunal—the first cousin of the Congress’ speaker—in an opaque and rushed process. Vizcarra argued that Congress’ action was tantamount to a no-confidence vote; his argument was deemed correct by most Peruvians, the national associations of governors and mayors, the security forces and groups of constitutional lawyers. The Organization of American States did not endorse Vizcarra’s argument but welcomed new elections. Vizcarra is emboldened; his new cabinet includes three close allies. His anti-corruption reforms will proceed. However, on Jan. 26, Peruvians will elect a new Congress, and it could prove unwieldy. Vizcarra has no party of his own. Although the previously dominant Fujimorista and APRA parties will fade, leftists and independents will rise and could complicate Vizcarra’s economic program, which has remained largely pro-market. There are uncertainties: re-election provisions are unclear and, although the Constitutional Tribunal is to rule on the dissolution in several months, its composition is unclear. Over the longer term, the hope is that a president’s right to dissolve Congress if it repeatedly and wantonly obstructs the executive will be respected. Also, the hope is that a president will not stretch this right into an abuse of power.”

Julio Carrión, associate professor and associate chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Delaware: “Was Vizcarra’s move to dissolve Congress justified? Legally, his decision is open to debate. Politically, he had no choice, because the fujimorista majority had dared him to do so by pushing with the controversial election of new members for the Constitutional Tribunal. However, little jurisprudence exists on the kind of issues that the president can pose as ‘questions of confidence,’ and therefore the legality of his action will eventually be decided by the Constitutional Tribunal. Vizcarra’s legal case was recently strengthened by the opinion issued by the European Commission for Democracy Through Law that correctly notes that the Peruvian Constitution ‘does not set forth any explicit limitations with respect to the issues which may be linked to a question of confidence.’ In addition, Vizcarra was not proposing a measure of constitutional reform—but rather a question of confidence regarding the procedures under which candidates for the Constitutional Tribunal are selected. When Congress proceeded to bypass his question of confidence, Vizcarra had no choice but to act. As expected, the public rallied overwhelmingly in favor of this action, with polls showing more than 80 percent of support for the dissolution of Congress. While perhaps justified in this case, Vizcarra’s move shows the extraordinary constitutional powers that Peruvian presidents have, which reflect a legacy of a constitution drafted to favor Alberto Fujimori. The political establishment had been unable to reform this constitution after the fall of Fujimori, and Vizcarra has shown how it can be used effectively to subdue Congress. Such disparity in executive-legislative relations is not good for the long-term health of Peruvian democracy. Today Vizcarra is employing this immense power for noble purposes. In the short term, this move has the potential to produce a Congress willing to engage in necessary political and anti-corruption reform, and this can only be good news for a system badly in need of reform. In the long term, this action may set a dangerous precedent for future presidents who may have more nefarious purposes.”

Jose E. Gonzales, managing partner at GCG Advisors: “The ‘tug of war’ between the executive and the legislative branches in Peru seemed to be a slow-motion affair meant to muddle any or all involved in the tussle for supremacy. On the day that President Martín Vizcarra dissolved Congress (Sept. 30), a series of rash decisions and confusing events led the rope to give way to the executive on the basis of a ‘factual denegation of confidence’ established by the appointment of a Supreme Justice by Congress. Constitutionally dubious, since it was based on a technicality, the decision was, perhaps, politically justified, assuming that Congress meant to vacate the presidency. Even though extremely popular, Congress’ dissolution, implemented quickly and without a clear plan for the ‘morning after,’ generates a series of governance complications regarding the four-month interregnum until a new legislative election in January 2020 and further on until the general elections of 2021, agitating political ghosts and current confrontations and introducing difficulty in any implementation of public policy initiatives. President Vizcarra is an accidental head of state who cannot count on a proper political organization and seems to lack, at times, a clear and firm strategy that would require the new Congress’ support to achieve success in its anti-corruption efforts, since the allowed executive decrees have severe limitations. Fortunately for Peru, all this political noise is not damaging the economy, which has been more affected by global dynamics than domestic politics so far.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue's Corporate Program and others by subscription.

With the recent decline in commodity prices, why have some countries have fared better than others?

Peru’s growing urban middle class is one of the country’s greatest assets, but it also brings political and governance challenges.

In Peru, it is generally known that a better quality education could build citizens, who are better prepared for the democracy and modern and flexible workers, who would help reduce poverty. However, over the last decade- as well during the previous one- many factors have prevented the improvement of the…

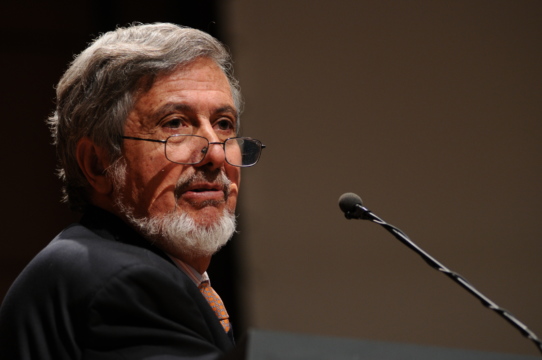

Vizcarra // File Photo: Peruvian Government.

Vizcarra // File Photo: Peruvian Government.