Latin America Advisor

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Has Colombia Found a Peace That Will Last?

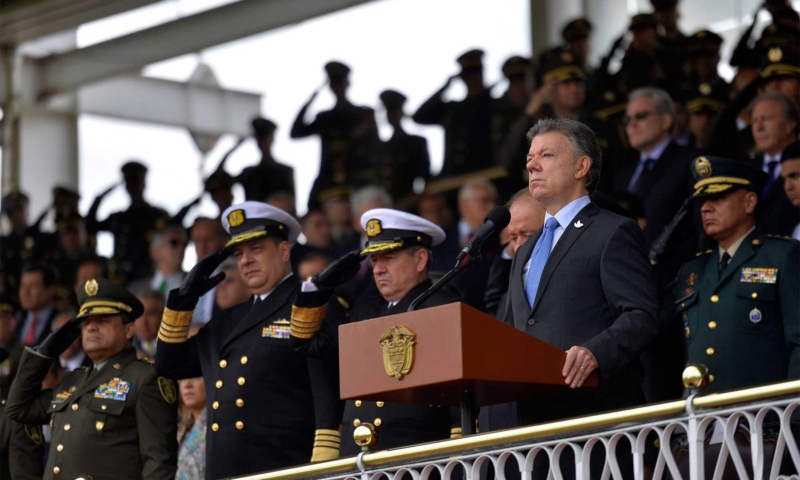

El Presidente Juan Manuel Santos rindió un homenaje a los soldados y policías caídos en combate en cumplimiento de su deber, durante la ceremonia de ascenso del General Jorge Nieto.

El Presidente Juan Manuel Santos rindió un homenaje a los soldados y policías caídos en combate en cumplimiento de su deber, durante la ceremonia de ascenso del General Jorge Nieto.

The Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia on June 23 signed a cease-fire, agreeing to end hostilities in their more than five-decade armed conflict. The signing took place in Havana, where the two sides began peace talks in November 2012. The cease-fire will take effect when a final peace deal is signed, which President Juan Manuel Santos has said he hopes will happen by July 20. Following the inking of the peace deal, the Colombian people would vote in a referendum for its passage. As the peace negotiations enter their final stage, how likely is it that the Colombian government and the FARC will be successful in convincing the rest of Colombia’s citizens to agree to the deal? What is the main thrust behind the opposition to a peace deal? What are the main obstacles to implementing the cease-fire and the other aspects of the deal, if Colombians do vote in favor of it in the referendum?

Marta Lucía Ramírez, former Colombian defense minister and foreign trade minister: "The negotiation agenda between the Colombian government and FARC advanced towards the ‘end of conflict’ as the bilateral ceasefire, cessation of hostilities and laying aside of weapons accord was reached. However, the absence of a definition of terms at the beginning of the peace dialogues allowed the FARC to continue to recruit children, keep hostages under their power, extort and participate in narcotrafficking. The lack of a conceptualization of justice that condemns all of those responsible for crimes against humanity, and additional requests from the FARC under the name of ‘provisos,’ or conditions, on which they are not yet agreed; crimes against soldiers and police officers in state of defenselessness; attacks on civilians and infrastructure, with the spilling of millions of barrels of oil into rivers; and armed political proselytism in La Guajira are all attempts to mitigate the emergence of true peace. It is difficult to measure the progress of negotiations, as the FARC has accepted to recognize the decision of the Court on the terms of plebiscite or agreement to leave aside weapons (although there is no inventory of them), and at the same time is insisting to negotiators that they should have the best results in justice, political participation and their responsibility for drug trafficking. FARC commanders claim to be senators without paying for their crimes against humanity and giving reparations to their victims. They could not take power by armed force and now seek to take it through politics. In this matter we cannot be naive and give them wrongful advantages to achieve their goal. Beyond predicting the success or failure of the government-FARC negotiations, I am convinced that we must invite all Colombians to read the accords with a sense of responsibility before voting ‘yes’ or ‘no’ in the plebiscite."

Adam Isacson, senior associate for the regional security policy program at the Washington Office on Latin America: "Even before the June 23 ceasefire breakthrough, polls showed a decisive, but not overwhelming, majority of Colombians inclined to vote ‘yes’ in an eventual plebiscite on a FARC peace accord. As it envisions the guerrillas fully disarming in six months, the new accord may increase that majority further. Still, hardline opponents of the negotiations have gained much media coverage and have used social media very effectively. They argue that the peace deal doesn’t punish FARC human rights abusers severely enough, that it will impose a leftist economic model in the countryside, and that the guerrillas could have been defeated on the battlefield. Their arguments, and President Juan Manuel Santos’ political unpopularity, may convince many Colombians to vote ‘no,’ or abstain from participating in a plebiscite. No matter what, implementing the peace accords will be difficult. The ceasefire phase will test the FARC leadership’s control over its fighters. Despite the presence of 300-400 United Nations observers, it may offer opportunities for would-be spoilers to attack demobilizing guerrillas. And it’s easy to imagine the complex, phased weapons handover falling behind schedule. Once implementation of the full peace accords begins, challenges will include resistance from paramilitary and organized crime groups, and their allies in local-level state institutions; anger at the slow pace at which the government, hampered by managerial shortcomings, is likely to act; and a lack of money, thanks to low oil and commodity prices, with which to pay for some expensive commitments."

John A. Cope, senior research fellow at the Institute for National Strategic Studies at National Defense University: "Assuming Colombians vote in a referendum on the passage of a final peace deal, there will be at least five different categories of voters with different mindsets about transitioning from war to peace. In each category there are people who seek justice for past deaths and destruction and others who seek peace and stability at all cost. Both groups will vote according to the perceived ability of the peace deal to realize their objective. It is difficult to anticipate the outcome. The categories include: 1) citizens living in large cities who remember feeling trapped and fearful but not personally threatened—President Uribe opened highways and brought relative peace to city dwellers 10 years ago; 2) citizens living in small cities, towns, and rural communities often with minimal government presence—they continue to suffer directly by violence and want stable governance; 3) citizens who have lost family/friends to violence or have been displaced—they tend to want justice; 4) citizens who support the FARC and its Marxist-Leninist ideology, live in areas dominated by the FARC, or have family members in the organization; 5) citizens on either side or third parties interested in exploiting opportunities for profit from the FARC’s demobilization. If the referendum passes, there are three immediate obstacles. First, the FARC must concentrate all forces in 23 ‘Transitory Hamlet Zones for Normalization’ and eight encampments, which challenge their command and control. Second, the government must grab control of FARC’s economic/drug zones and deny access to BACRIM, the ELN and others. Third, Bogotá must find ways to convince communities across the country to accept the reintegration of FARC members. These will all be difficult challenges."

Juan David Escobar Valencia, director of the Center for Strategic Thought at the Universidad EAFIT in Medellín: "Like the myth of Pandora’s Box, so goes the negotiations with the FARC terrorist group, and the recent ‘bilateral ceasefire.’ While they may appear to be magnificent gifts, the moment you open the box, out jumps a whirlwind of evils. The ceasefire agreement is not as detailed as it’s been sold to be. I’ll detail some of its dangers here: 1) The agreement does not have any mechanism for certifying the number of weapons the FARC has and that they are going to hand over. 2) The FARC has not assumed any responsibility for the use of landmines, which are weapons of war. 3) For more than a year now, the FARC has been outsourcing weapons, men and illegal activity to the ELN terrorist group, allowing the FARC to appear inactive while continuing to control illicit business and mass extortion of the population that has been unleashed during the negotiations. 4) The document of the bilateral ceasefire supposedly leaves the guerillas inactive, but the exact terms leave at large at least half of the FARC’s members. 5) The timetable for the staggered surrender of the weapons that the FARC decides to turn in shows that the plebiscite will take place during the period where the FARC will still have most of its weapons. 6) The peace agreement that is being negotiated does not oblige the FARC to return its enormous funds, which amount to billions dollars. This means it’s impossible to guarantee that the FARC will not acquire more arms in the future."

Maria Velez de Berliner, president of Latin Intelligence Corporation: "There is not a Colombian who would prefer war over peace. However, many see the terms of the cease-fire and Zonas Veredales Agreement as the government’s legalization of the crimes committed by the FARC’s Central Command, its guerrillas and militias. Remembering the FARC’s motto, ‘From Marquetalia to Victory,’ Colombians who oppose the agreement see the Zonas Veredales as 23 different Marquetalias, zones of FARC’s criminality and illegality. But the Santos government will win the plebiscite, turning the final peace agreement into national and international law. However, its implementation is fraught with risks, principally, for a few reasons I will now detail. The agreement covers neither the totality of the FARC nor the thousands of criminal organizations that today undermine peace and security all over Colombia. It is an agreement between Santos’ government and the FARC’s Central Command that leaves out different FARC frentes that operate in Colombia and neighboring countries, and FARC-associated criminal organizations, such as the Cartel del Golfo (a.k.a. Urabeños/Úsugua Clan), Pelusos, Puntilleros, ELN, EPL and hundreds of Combas. These organizations control the downtown areas of critical urban centers and rural and coastal areas. Consequently, a majority of Colombians believes there will not be peace and security, but constant mini-wars, such as those being waged now in Antioquia/Chocó, Catatumbo, and Cauca. Unleashing the demobilized FARC to eliminate criminal organizations, as ‘Timochenko’ stated in his Havana speech, reminds Colombians of the AUC and the havoc they wrecked. Demobilized AUCs created the BACRIMS (criminal gangs) or joined the FARC! No one denies that peace is wanted and needed. But, after 52 years of fratricidal war, rampant corruption, and collusion, Colombia lacks the nationwide legal, political, social, cultural, economic, and security strengths necessary to implement these agreements. May the Santos government be able to create those strengths or Colombia will otherwise plunge into criminality and violence greater than exists today."

Jorge Lara-Urbaneja, partner at Arciniegas, Lara, Briceño & Plana in Bogotá: "Since the peace talks between the FARC and the Colombian government started in 2012, there have been a number of adjustments that allowed the FARC to increase and promote its lines of business, mainly illegal mining and drug crops and production. Presence throughout the whole country and control of the territory are the most important aspects of maintaining the FARC’s activities. The cease-fire documents signed in Havana formalized the FARC’s presence, well-equipped, in all areas of their interest. International drug logistics and distribution is already established in Venezuela, an appendix of Cuba. In this scenario, there was no point for the FARC to continue filling newspapers with town destruction and crimes against peasants and small communities. However, drug activities and illegal mining will always require violent actions, as well as drafting and training children in the business. But, for that aspect of the group’s operations, there are the ELN and other specialized organizations, which have grown at the pace of Colombia regaining its position as a major drug-producing country in the world. However, the FARC will continue fostering extortion activities, mainly in those areas where the government plans to promote agricultural and cattle programs. Evidently, the peace negotiations and results have raised a lot of criticism throughout the country mainly because in order to reach an agreement, the government has dropped important legal and constitutional principles. The final peace agreement is supposed to reform Colombian institutions, but in aspects not yet disclosed and discussed. And last but not least, it has been too long a process with too dark conclusions."

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue's Corporate Program and others by subscription.