Book: China’s Latin America partners are engaging on new terms

China-Latin America expert Margaret Myers talks about her new book on how China is changing its approach across the continent.

A Daily Publication of The Dialogue

Peruvian Trade Minister Eduardo Ferreyros on Feb. 6 defended China as a good trade partner for the South American country. His comments came days after U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said in a speech that “China’s offer always comes at a price” and cautioned Latin American countries against reliance on “new imperial powers that seek only to benefit their own people.” Are Latin American countries relying too much on China? What are the main benefits and drawbacks countries are experiencing from their economic and political links with China? What factors have led to increased Chinese investment and influence in Latin America? How does China’s approach to engagement with Latin America differ from that of the United States?

Jorge Heine, public policy fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington and a former Chilean ambassador to China: "China is now the top trading partner for Brazil, Chile, Peru and Uruguay, and the second-largest trading partner for many other Latin American countries. In 2017, Chile and Uruguay exported more to China than they did to the United States and the European Union combined. Some 27 percent of Chile’s exports go to China, as do some 28 percent of Uruguay’s. Is that too much? Given that China has accounted for about a third of the world’s economic growth over the past decade, and that in 2017 it grew at 6.9 percent, three times as much as the United States did, this should not be surprising. You sell your goods where there is demand. Projections indicate that by 2050 half of the world’s GDP will be in Asia, so this trend is likely to increase. China provides a ready, growing market for Latin American goods, and Chinese demand for them was one reason the region was able to withstand the 2008-2009 financial crisis so well. Some argue that Chinese demand for the region’s natural resources has an adverse effect on Latin America’s industrialization. This is putting the cart before the horse. If countries wanted to industrialize, they could apply industrial policies, relying partly on the rents generated by growing trade with China. But they are unwilling to do so. China’s presence in the region is the natural product of its being the world’s second-largest economy, its thirst for commodities and its need to export capital. For a region traditionally dependent on the United States and Western Europe, China provides a welcome opportunity to diversify its trade, investment and diplomatic links, links that come with no strings attached."

Matt Ferchen, non-resident scholar at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy in Beijing: "Secretary Tillerson’s warning to Latin American countries to be wary of China’s role in the region is best understood as part of a broader pushback by the Trump administration against the perceived threats of China’s mercantilist economic statecraft around the world. Yet the timing and content of his comments are both misconceived. American credibility with its southern neighbors is at a low ebb, given President Trump’s hostility toward Mexico and toward Latino immigrants in general. At the same time, claims of Chinese mercantilist practices in Latin America are largely off base given that trade ties, which in some South American cases certainly have exacerbated concerns about heightened commodity dependency, have mostly capitalized on simple comparative advantage. No matter the timing, American lectures to Latin Americans on how to conduct their foreign policy are self-defeating. If anything, it is Trump administration policies and attitudes that have provided China a rhetorical opening in Latin America at a time when China’s economic and political relations with the region face serious challenges. In the post commodity boom era, the ‘win-win’ trade story is no longer as easy to sell to Latin American publics, while promises of Chinese investment and infrastructure deals often fail to meet the hype. But as always, Venezuela remains the most difficult economic and political challenge for China, and it is here where the trading of diplomatic jibes between the United States and China is most unproductive. Along with Venezuela’s Latin American neighbors, American and Chinese interests in helping Venezuela move off the path of self-immiseration should create, not foreclose, an opening for creative diplomacy."

Francisco Durand, professor of political science at the Catholic University of Peru: "Tillerson’s critical reference to China is only the latest American reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine, which surprises no one in Latin America, particularly given the ‘America-first’ orientation of the Trump administration. The question is more what alternatives the region has when it comes to strong economic actors. The most enduring approach has been to ‘diversify’ economic relations. China fits that category, in particular when it provides an alternative market source. Yet, it does come at a price. China is continuing penetration in two areas: importing critical raw materials for its economy and exporting manufactured products. Chinese companies have different sets of standards, and some are more modern than others. The problem is that regulations are poor and often, when questions arise, government regulators sense that behind the company there is a superpower with political connections that inhibits them from tightening the regulations affecting Chinese companies. In terms of massive Chinese imports, as in many other countries, the concern is dumping, particularly in textiles and shoes, together with products that have low safety standards and questionable quality. Here, Peruvian producers face tough competition and absence of state regulation. In political terms, the Chinese companies usually operate initially with Chinese-Peruvian nationals but also have ties with all political parties, who travel often to China. Although China’s presence here is recent, it has been growing steadily since the 2000s. It jumped in Peru and the rest of the region during the 2008-09 international crisis, reinforcing the conviction that it is good to have alternative markets. In terms of international relations, China presents itself as a ‘Third World country’ that has more in common with the region and whose policy, the Beijing Consensus, is quite the opposite of what Tillerson presents: a reliable partner with no imperial ambitions, willing only to do business, slowly and persistently strengthening ties with its new friends. Now there is more than one giant, and lately, China has one more thing to offer: development of infrastructure, trains in particular."

Ricardo Barrios, program associate of the Latin America and the World program at the Inter-American Dialogue: "The extent to which Latin America relies on China varies on a country-by-country basis. Brazil and Argentina, for example, rely heavily on China as an export destination for agricultural goods, especially soy, but this does not hold true for other economies. China is also a top destination for Peruvian and Chilean copper. While Latin American countries have benefited from exporting large quantities of primary commodities to China, it is unclear whether this model of trade will support economic development in the long term. Some other Latin American nations, such as Venezuela, have been rather dependent on China as a source of credit. China’s motivations for engaging with the region are increasingly complex and range from domestic concerns and policies (for example, China’s ‘Going-Out’ strategy and President Xi’s supply-side reforms) to foreign policy imperatives (such as the Belt and Road Initiative). In this respect, China’s policy-driven engagement with the region stands in stark contrast to the United States’ less integrated approach. The U.S. approach is arguably less cohesive, but its focus on strengthening institutions and increasing productivity through private-sector actors has made for more diversified engagement with the region. According to information collected by the World Bank Group, for the year 2016, raw materials made up fewer than 12 percent of the United States’ imports from the region, the bulk of which were capital goods (46 percent) and consumer goods (28 percent). Imports from the United States to the region were also split nearly equally between consumer, capital and intermediate goods."

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue's Corporate Program and others by subscription.

China-Latin America expert Margaret Myers talks about her new book on how China is changing its approach across the continent.

China is increasingly relying on public diplomacy to support its economic engagement in the region. The country’s state media already plays a significant part in promoting a productive relationship with Latin America.

Since 2010, a series of Chinese government policies has supported the development of increasingly high quality Latin American and other area studies centers across the country, primarily in an effort to inform China’s foreign policy-making.

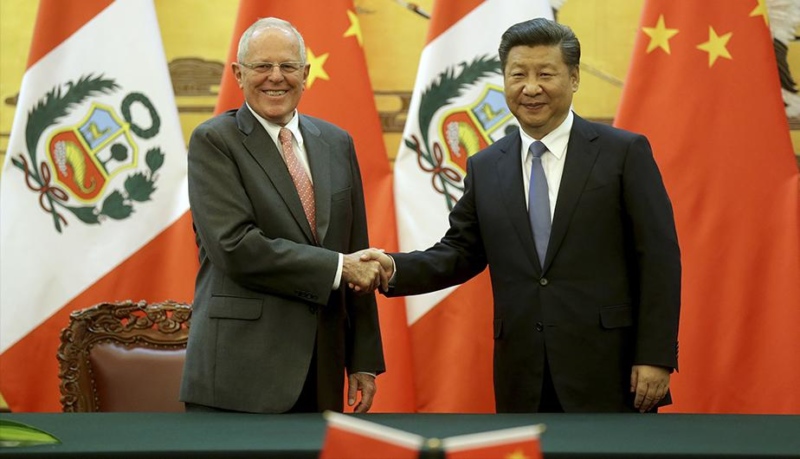

Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (L) meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping

Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (L) meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping