This post is also available in: Español

Parliamentary Elections and Their Meaning

The parliamentary elections that took place in Venezuela on December 6th (6D) of last year resulted in the most significant electoral defeat for chavismo since its first victory in 1998. This poses the question of whether the result was due to a structural breakup of the electorate vis-à-vis chavismo or if it was a momentary, short-lived reaction to Venezuela’s current economic crisis.

The 2007 and 2010 elections served as an important precedent to the opposition’s victory in the 2015 parliamentary elections. These elections were characterized by three common factors. First, former President Hugo Chávez’s leadership was not at stake; the 2007 elections were about radical constitutional reform and the 2010 elections were for National Assembly seats. Second, both elections experienced a significant reduction in electoral participation, directly proportional to the reduction in the chavista vote. Lastly, in both cases, the subsequent elections centered on Chávez: the 2007 elections were followed by the 2009 reform, which aimed to grant Chávez the power to be reelected indefinitely; and the 2010 elections were followed by the 2012 presidential elections.

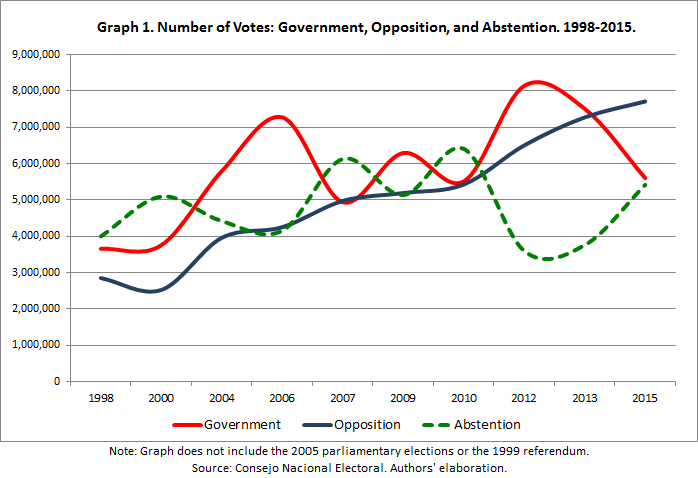

Chávez’s prominence in the 2009 and 2012 elections helped increase electoral participation, as well as the number of chavista votes. Graph 1 clearly shows the relationship between abstention rates and chavista votes, both variables marked by large and inversely proportional volatility. In other words, instances involving the largest number of chavista votes have also been those with the lowest abstention rates, and vice versa. The greatest number of chavista votes (and lowest abstention rates) recorded happened during the 2006 and 2012 presidential elections, as well as the 2009 referendum for constitutional reform.

On the other side of the spectrum, the opposition vote has experienced an uninterrupted upward trend since 1998, regardless of both abstention rates and type of election.

Before the 2015 parliamentary elections, chavismo’s attempts to place Hugo Chávez’s image at the campaign forefront (“Nosotros con Chávez”, “El 6D otra vez gana Chávez”, “Lealtad al legado de Chávez” were campaign slogans used repeatedly by the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela, PSUV) did not yield the expected results.

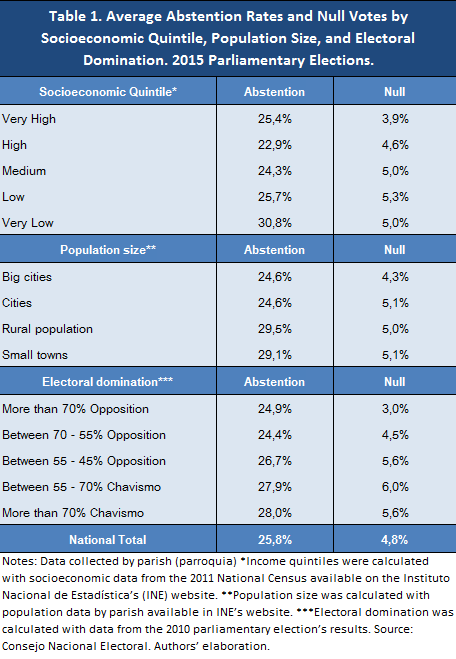

It could be argued that three behaviors jointly contributed to the opposition’s victory by nearly 2 million votes: (a) an increase in abstention; (b) an increase in null votes; and (c) changes in electoral preferences

Abstention increased relative to the 2013 presidential elections, though not in a homogeneous way. The most significant increases took place in areas of chavismo domination (traditionally more than 55% of the votes), characterized by lower socioeconomic levels, smaller populations, and rural settings. The same trend was also present in null votes (see Table 1).

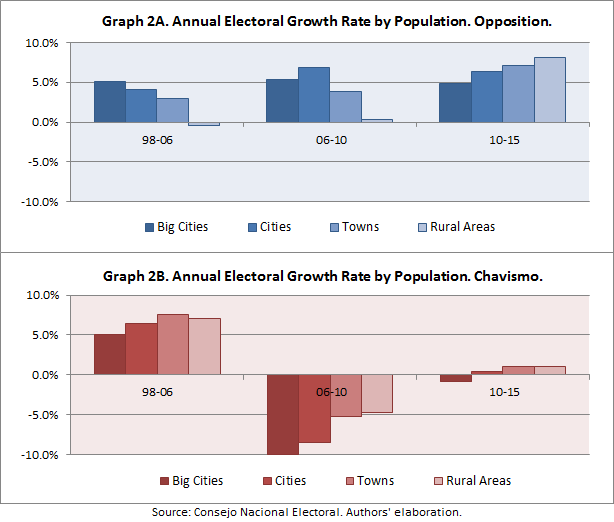

The opposition achieved unprecedented growth in these areas in recent years, consistent with the classic “center to periphery” modernization process (see Graph 2A). In the 1998-2006 period, the largest opposition gains took place in Venezuela’s big cities, while electoral growth in the country’s rural areas was much smaller and sometimes even negative.

Between 2006 and 2010, the opposition increased its electoral growth rates in the country’s smaller cities and large towns, but failed to penetrate the rural areas. In the five years leading up to the 2015 parliamentary elections, the opposition experienced inverse growth relative to the initial 1998-2006 period, finally reaching the country’s most rural areas. The rural support translated into the opposition’s greatest increase in votes, greater than in any other areas or previous periods, marking the breakdown of chavismo’s traditional strongholds.

On the other hand, during its initial rise, chavismo was notably characterized by greater support in rural areas and small towns, and a significantly smaller urban presence (see Graph 2B). In the subsequent period, its growth rate tended to decrease, primarily in the urban areas, but also in rural areas, at a slower pace. The third period demonstrates clear stagnation.

The data clearly shows that the 6D electoral results in Venezuela are more than just an expression of social unrest due to a faltering economy dependent on oil revenues. Even as the economy falls into crisis, giving way to the so-called “voto castigo” (punishment vote), the data reveals the fragility of a political movement built around a single figure: Hugo Chávez.

Post-Electoral Scenarios

Post-electoral scenarios are tied to the evolution of the opposition alliance as well as the chavista alliance, both of which are continuously tested.

Challenges within the opposition

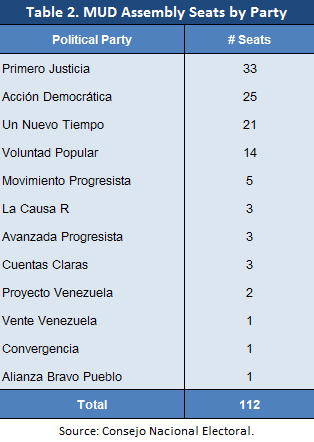

The opposition alliance, Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD), garnered 59% of the votes in the 6D parliamentary elections, which secured two thirds of the seats (112/167) in the National Assembly (AN). This “qualified majority” is the most determinant possible, ensuring the MUD has absolute control over the legislative branch.

One of the main challenges for the opposition in this new phase will be the relationship MUD–AN. Before 6D, the MUD had a common agenda with shared objectives, notably obtaining a victory in the parliamentary elections. However, the parties comprising the alliance continued to operate in a relatively independent manner.

The dynamic now changes. The AN’s recently elected opposition leaders currently represent the popular vote and have real, tangible power inside the Venezuelan state. In order to legislate, the representatives will have to set aside individual agendas and build consensus for joint decisions. This requires sacrificing ideological stances, accepting decisions for the greater benefit of the alliance in spite of conflicting personal or partisan interests, and, most importantly, thinking about the best possible path for the country.

The 6D victory has created significant leadership roles for the four main parties of the opposition alliance: Primero Justicia (PJ), Acción Democrática (AD), Un Nuevo Tiempo (UNT) and Voluntad Popular (VP), known as the G4 (see Table 2).

Looking beyond the parties, some individual leaders elected to the AN have increased their popularity levels, specifically Julio Borges (PJ), Enrique Márquez (UNT), Freddy Guevara (VP), and, perhaps most significantly, Henry Ramos Allup (AD), who assumed the presidency of the AN. These political figures join some of the most prominent opposition leaders of recent years, notably Leopoldo López (VP), Henrique Capriles Radonski (PJ), and Manuel Rosales (UNT), who continue to hold emblematic stances within their own parties. This suggests that a coordinated strategy by the opposition must take place not only among parties, but also within them.

Other opposition leaders have also assumed important leadership roles in recent years. María Corina Machado (Vente Venezuela, VV), who after the “La Salida” experiment, co-led with Leopoldo López and Antonio Ledezma, has furthered her agenda, and is determined to increase her national presence, recently asserting her aim to be “the first female President of Venezuela”. Liborio Guarulla (Movimiento Progresista de Venezuela, MPV), current Governor of Amazonas, and Henri Falcón, current Governor of Lara, have also positioned themselves as important allies of the MUD. While both have a chavista background, they currently rule two of the three states that comprise the MUD alliance (Capriles governs the third, Miranda). Additionally, Jesus “Chúo” Torrealba’s leadership is also notable. As MUD’s secretary general since September 2014, Torrealba has become a key player in the opposition’s accomplishments over the last year and a half.

In the midst of this growing, heterogeneous opposition leadership, several questions arise. How will legislative priorities be defined? Who will have greater power, the president of the National Assembly or collective presence of Primero Justicia, which is the party with the greatest number of seats? Before 6D, the common goal was clear: the MUD needed to obtain the highest possible number of Assembly seats. In other words, the objective was to defeat PSUV. Now that this has been accomplished, what will be the alliance’s priorities? What is the MUD’s current agenda? Will the unidad remain strong in future gubernatorial, mayoral, or even presidential elections.

Potential breakups within the government

The 6D results represented chavismo’s most significant electoral defeat in the last 17 years. Beyond the evident economic crisis that fueled the “voto castigo”, one of the main reasons for the opposition’s victory (or chavismo’s defeat) was the growing division within the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV). This internal conflict can be evaluated from three different perspectives: vis-à-vis the economic crisis, the electoral process, and the executive branch.

From the economic standpoint, a clear breakup took place within chavismo when several officials who were close to Hugo Chávez left office once Nicolás Maduro became President. For instance, Jorge Giordani, Chávez’s main economic advisor, left the administration two months after Maduro’s victory, expressing his clear discontent with the regime in his “testimony and responsibility with history”, published in June 2014. Giordani denounced, among many other issues, the high levels of corruption and wasteful spending, as well as characterizing Maduro’s lack of leadership as an “apparent power vacuum in the Presidency”. Other former officials that have publicly opposed Maduro, especially on the economic front, include Rafael Isea (former Finance Minister) and Héctor Navarro (Former Education and Electricity Minister).

Additionally, in the midst of the economic crisis, there are clear fractures and instability in the management of the country’s economy that do not necessarily have to do with Chávez’s former officials. For example, Maduro has just replaced the newly named Minister of the Economy, Luis Salas, after only forty days in the position. Businessman Miguel Pérez Abad, who currently serves as Minister of Industry and Trade, has taken over the position. These sudden changes reveal the pressure that the executive branch is under, as well as their lack of coordination in executing economic decisions.

From the electoral perspective, the votes against the party were a manifestation of internal divisions within PSUV. The strategy of party leaders was consistent with that of previous elections: the excessive use of Chávez’s image, state resources, and public media outlets, as well as the design and implementation of intimidation (e.g. threats to public servants) and deception tactics (e.g. Partido MIN-Unidad). What did change was the response by the party’s popular base. People did not mobilize with the same energy and conviction as in previous elections. Areas previously dominated by chavismo experienced a shift and voted for opposition candidates.

It is important to recognize that, even with the adverse conditions the country is currently experiencing, PSUV still managed to garner 41% of the popular vote – more than what any individual opposition party achieved. In other words, PSUV is still Venezuela’s most popular party, which, in times of socioeconomic crisis, can be interpreted as a remarkable display of unity. Nevertheless, it is also worth noting that some of the government’s tactics of fear, intimidation, and deception played a role in the elections. Several private surveys argued that a significant number of PSUV votes came from citizens who feared losing their public sector jobs, pensions, study abroad scholarships (e.g. parents of youth studying overseas), or social program benefits (e.g. Misión Vivienda).

It is also worth emphasizing that many of the Venezuelans who voted against the government do not necessarily favor the opposition. This reality poses challenges for both chavismo and opposition. For the former, it could be a sign of the rise of an alternative to Maduro from within chavismo (from both its popular base and its leadership). In fact, several surveys indicate that while Maduro’s popularity has declined, Chavez’s legacy remains much stronger. For the latter, it is an indication that while many disgruntled citizens voted for the opposition candidates, their plans and proposals are still not sufficiently convincing. A new movement within chavismo could be open to dialogue with the opposition; however, this could result in the intensification of more radical leaders within the government, which could potentially aggravate the current contentious situation.

Beyond the constant shuffling in leadership of the executive branch, a potential break within chavismo’s elites took place on January 29, 2016 during the Second Extraordinary Plenary of the III PSUV Congress. On that day, as explained in an article by Franz von Bergen, Research Coordinator for El Nacional, Maduro announced the elimination of the regional vice-presidencies and the appointment of twenty-four “responsables políticos” (political representatives)–a measure that reduces the power held by governors over the party in their respective states. It is worth remembering that the twenty-one PSUV candidates elected as governors were directly appointed by Chávez at one of his last public acts. Some believe that with this new measure Maduro is attempting to reduce the influence of figures close to Chávez to limit his internal political opponents, particularly certain military leaders.

Of the twenty-four appointees, fifteen have direct loyalty ties to Maduro, six seem to answer to groups different from Maduro’s (especially to Diosdado Cabello), and five appear to have power of their own. An interesting statistic indicates that 52% of chavista governors come from the military, while only 21% of the new PSUV state appointees designated by Maduro come from the barracks, according to von Bergen. These structural changes in chavismo become increasingly relevant as the 2016 state elections near.

Conclusions

The 6D electoral results indicate much more than a discontent stemming from a decline in quality of life. They show a structural transformation of the Venezuelan electorate, which following the death of former President Hugo Chávez, is in the process of redesigning its political affiliations. Keeping in mind the upcoming electoral calendar (governor elections in 2016, mayor elections in 2017, and presidential elections in 2018, with the possibility of an anticipated recall referendum), the outlook remains unclear for the two main political alliances in Venezuela: MUD and PSUV.

While the opposition has seen a trend of steady growth and handed chavismo a significant defeat in the parliamentary elections, the alliance will face a greater challenge of internal cohesion as it inches closer to power, particularly the presidency. Opposition collaboration within and between parties, both inside and beyond the National Assembly, will be both a key challenge and a prime opportunity to generate change in 2016.

Meanwhile, chavismo will be put to the test when the chavista alliance is faced with the question of how far it is willing to go to retain power. After losing a considerable fraction of popular support in a worsening economic environment, chavismo is obligated to collaborate within its own party and with external actors. Their challenge will be to regain internal coherence, generate enthusiasm among their followers, and find a way out of the economic debacle.

Hector Briceño is Chief of the Sociopolitical Division at the Center for Development Studies at Universidad Central de Venezuela (CENDES-UCV). Contact: hbricenomonte@gmail.com. Twitter: @hectorbriceno. Federico Sucre is a Program Assistant at the Inter-American Dialogue. Contact: fsucre@thedialogue.org. Twitter: @FedeSucre.