Central America’s Great Crisis

This post is also available in: Español

Confidencial

Confidencial

Central America is experiencing one of the most severe crises in its history. While it is no longer the era of Somoza or Rios Montt, and elections are freer and fairer than in the past, the region as a whole is facing important problems.

The number of deaths in the region, for example, has been higher in the past 10 years than in the decade of the 1980s. Even in Nicaragua, which is often outside the international spotlight, violence is a very real phenomenon. Democratic governance is infected by continued abuse of authority and political corruption. The economic development of the region in the 21st century remains stagnant, with high levels of poverty and inequality. Environmental damage continues to be prevalent. Adults and children alike are fleeing from their countries, and migration continues to be a biproduct of poverty, crime, corruption, and abuses of authority. In short, now is the time to take the crisis in Central America more seriously.

Violence

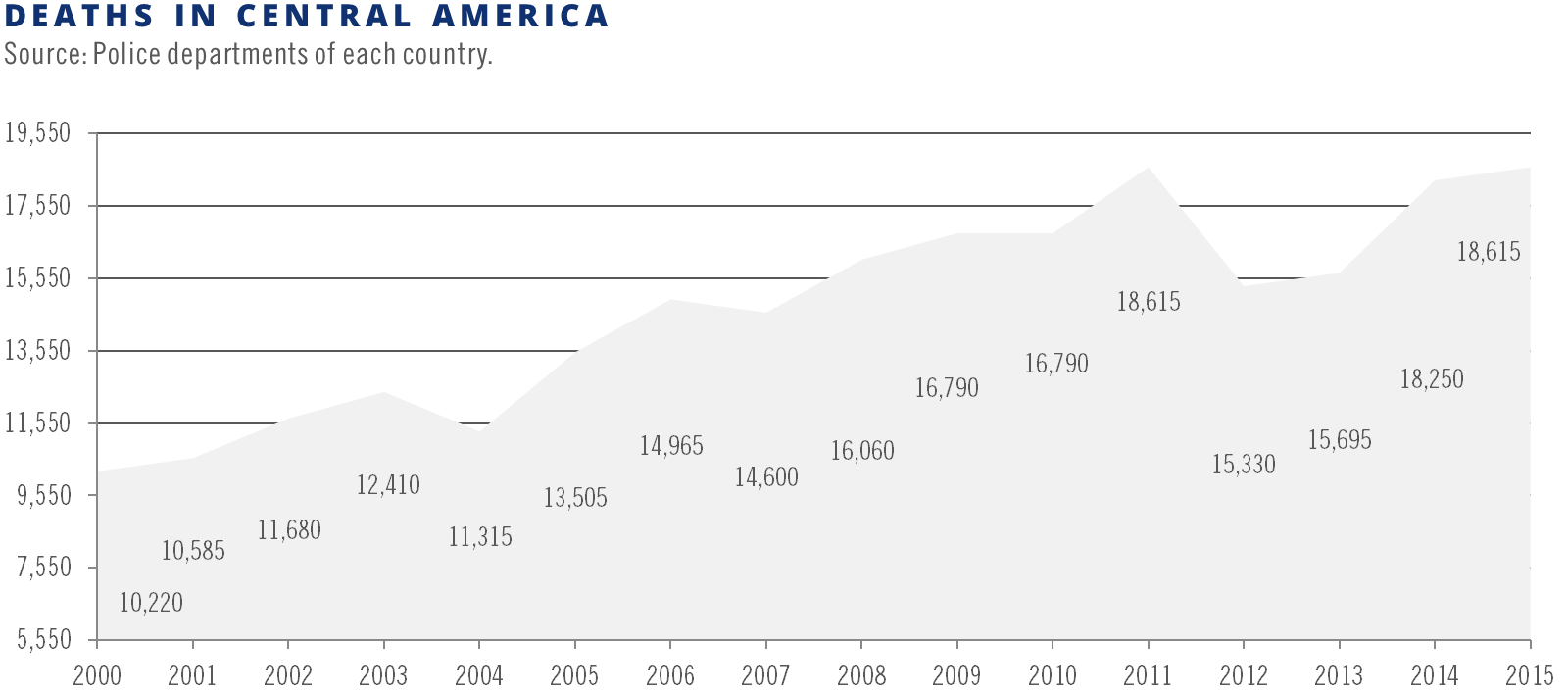

Although historical records suggest that the decade of the 1980s was the most violent in Central American history, homicide figures from the last 15 years point to new trends in violence that are far greater. For example, El Salvador experienced 70,000 fatalities during its civil war, and Guatemala more than 100,000. Between 2000 and 2014, however, more than 200,000 Central Americans have died due to violence in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Nicaragua has experienced violence as well, albeit to a lesser degree, in the form of intimidation and threats. These deaths are caused by several factors, but in particular, by the presence of an ecosystem of organized crime that includes armed gangs, extortionists, kidnappers, and drug traffickers that move narcotics with their own private militias. It also includes mobs organized by political groups and leaders, as in the case of Nicaragua.

Questionable Governance

The exercise of political authority in the region has been contaminated by corruption, human rights violations, and the abuse of power. The resignation of Guatemalan President Otto Perez Molina serves as one example of this type of lawlessness and corruption. In Guatemala as well as in Honduras, fraud against the public has been horrific. In the case of “La Línea” alone, Guatemala lost more than US$350 million, not unlike the case of Social Security fraud in Honduras. This represents 5% and 10% of total public spending in Guatemala and Honduras, respectively. In Nicaragua, the lack of transparency is even more apparent: there is no accountability for the more than US$3 billion coming from so-called “state cooperation” with Venezuela. And these are only a few of the most recent examples. In El Salvador, gang activity has paralyzed the economy and the public through a multi-million dollar extortion scheme, threatening households and businesses across the country. With no less than 30,000 active gang members, gangs terrorize even their own neighbors with the threat of death.

Persistent Poverty

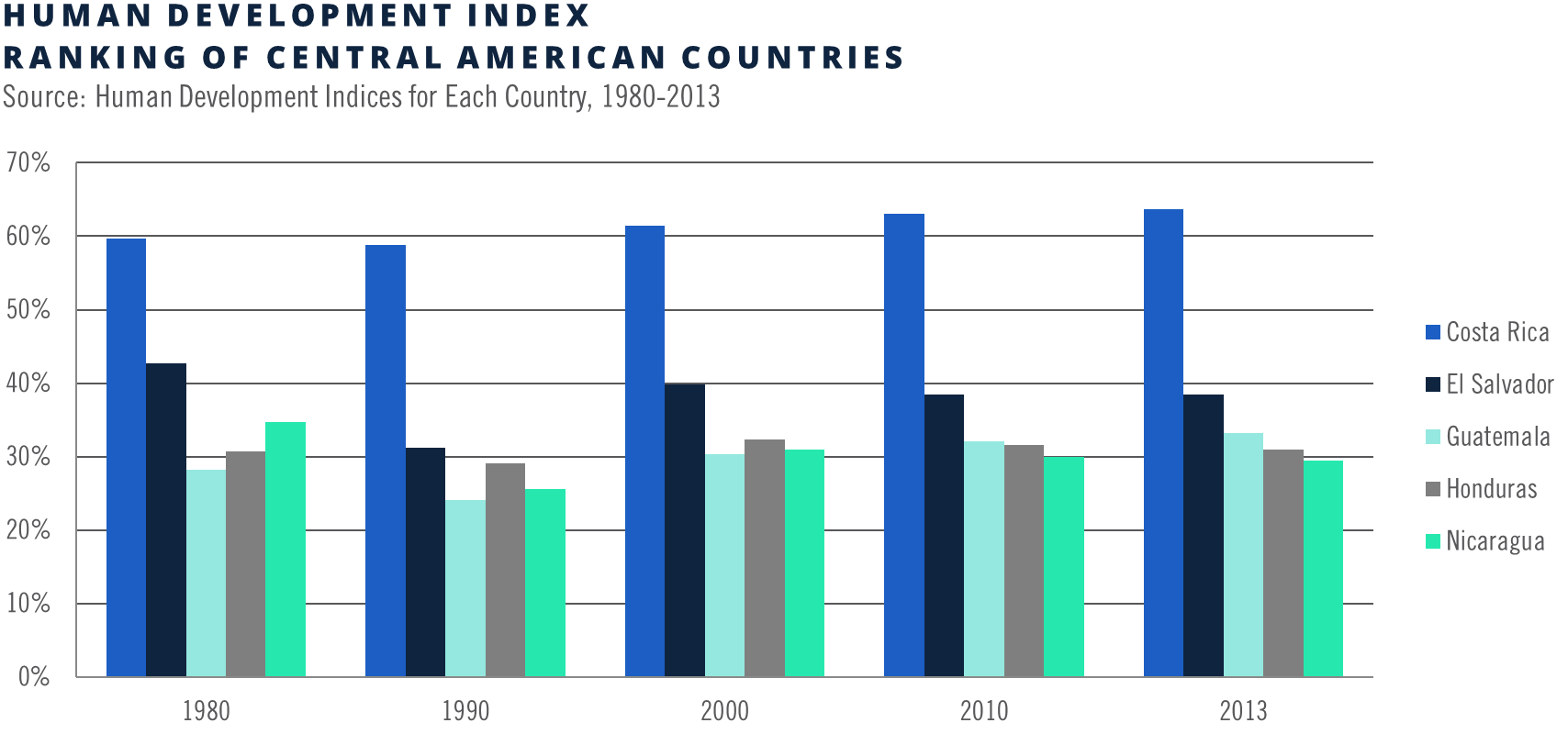

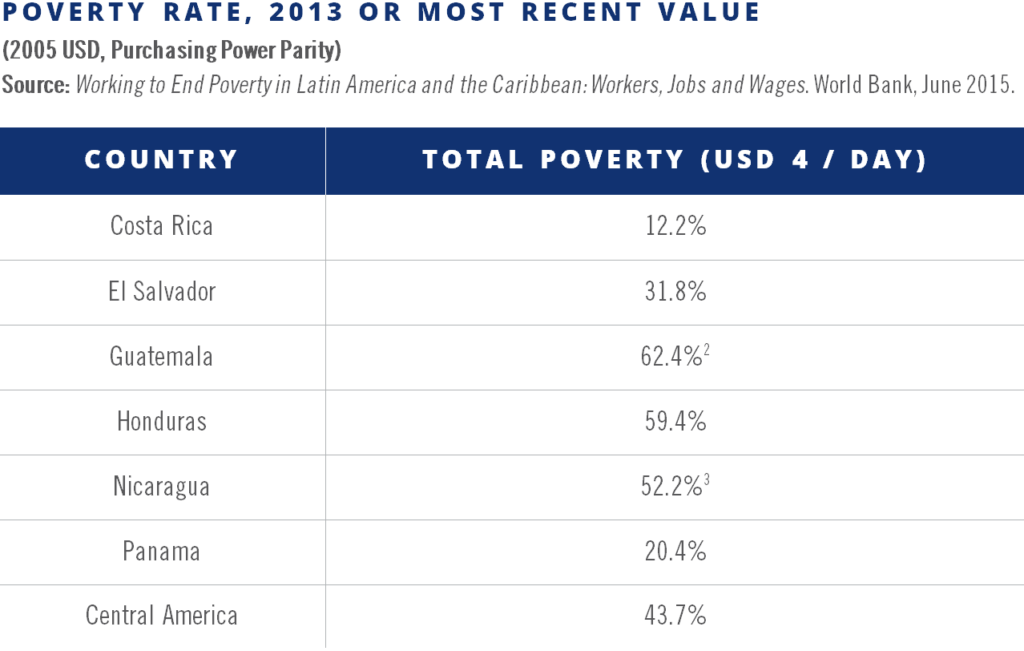

In spite of living in the digital age, Central Americans continue to experience high levels of poverty. More than half of the population lives on less than US$4/day in societies that are, in many cases, highly unequal. This poverty is not new. As the Human Development Index shows, since 1980 there has been little substantive improvement among Central American countries. Moreover, Nicaragua’s percentile ranking in human development has fallen more than it has increased from 1980 to present. Although human development is dynamic, not static, our societies have not adjusted to global changes associated with human capital. They remain regionally myopic regarding human well being and development priorities. The region’s labor force continues to be low-skilled, un-educated, highly informal and poorly paid. It is almost impossible to grow out of poverty with economic models that are built on low-skilled, uneducated and informal labor.

Mass Migration as a Consequence

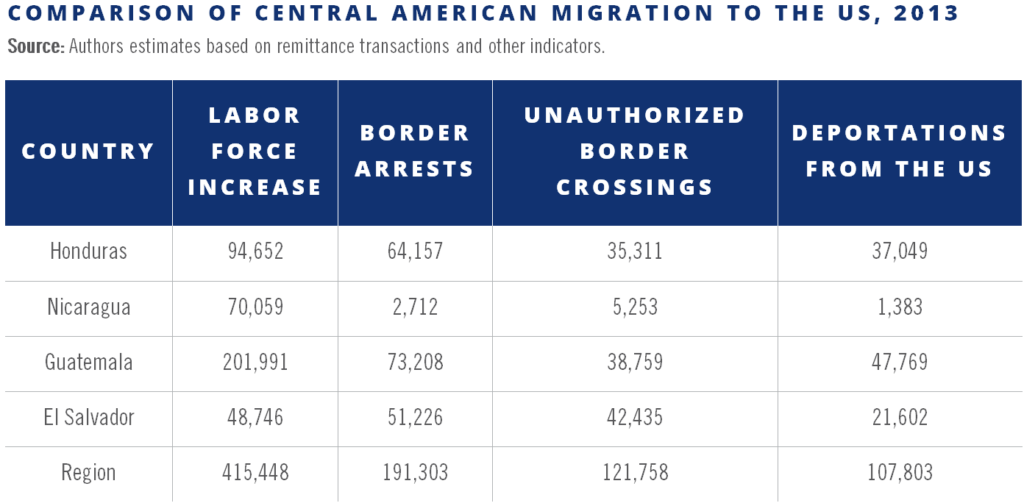

The present circumstances offer little for those who choose to stay in their countries. In a nationwide survey conducted in El Salvador in 2014, more than a third of respondents said they were thinking of emigrating. And in reality, at least 200,000 people are leaving their countries each year. The number of Central Americans entering the US alone amounts to at least 130,000 people annually. However, this figure does not include those who are detained at the border with Mexico and the United States, amounting to more than 200,000.

To put this into context, it is important to note that the annual growth in the region’s labor market is close to the number of people trying to migrate. Those that manage to enter the United States represent 30% of the annual increase in the labor market! Nicaragua is no exception to this: unlike its northern neighbors, Nicaraguan migrants generally head to Costa Rica, and nearly 100% manage to “successfully” cross the border. More than 15,000 Nicaraguans enter Costa Rica each year, though the magnitude of this exodus is often ignored.

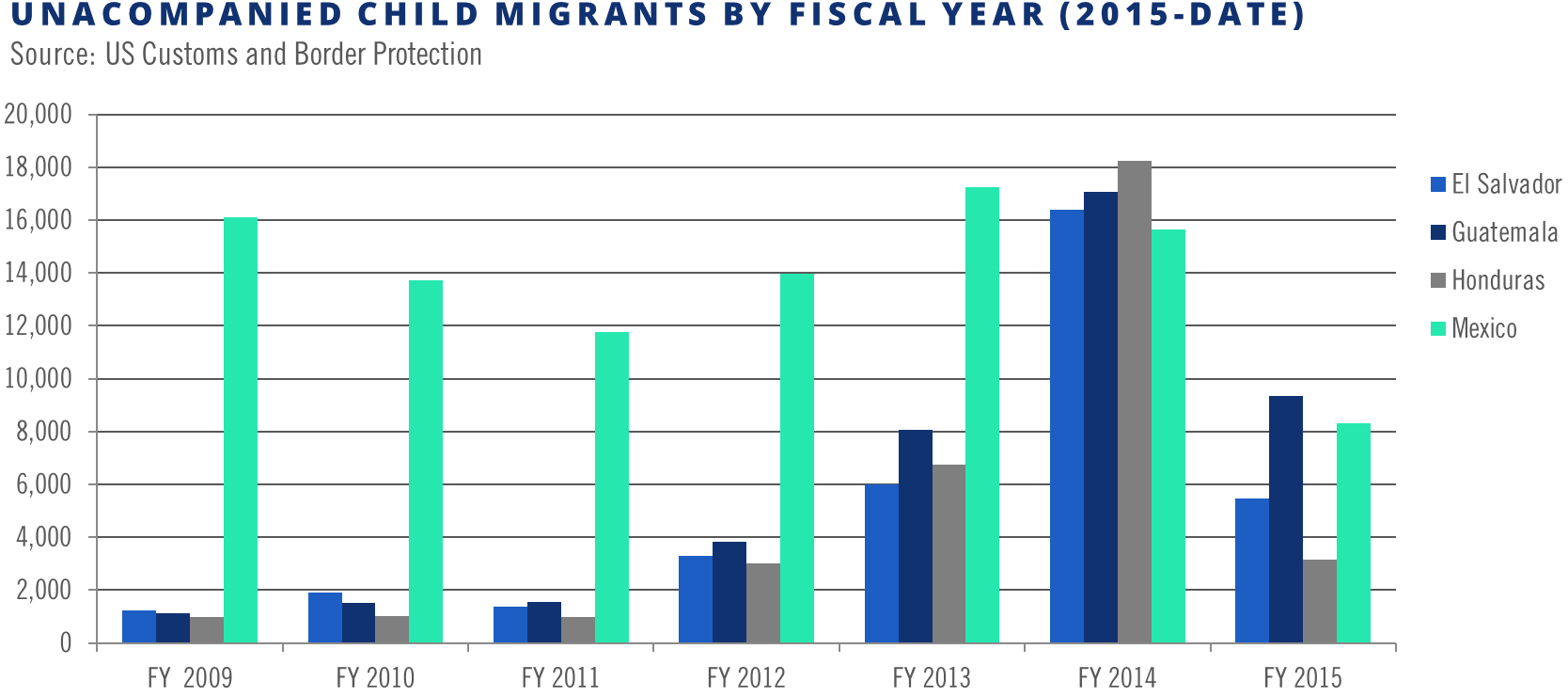

It is also important to note the sizable number of children and youth that are fleeing from their countries in search of opportunities and safety. This issue caught the attention of US policymakers, human rights organizations and media outlets in the summer of 2014, but it is unfortunately nothing new. Although FY 2014 saw record levels of unaccompanied child migrants from Central America entering the United States (more than 40,000), FY 2015 has seen a 30% decline compared to 2014, with 25,000 cases. Still, children and youth continue to leave their countries.

The Urgency to Act

How many more people will have to die, to flee from home, and to live in poverty before the crisis in Central America is taken seriously by its leaders? Central America is not moving forward, but rather backwards. Its leaders, as well as the international community, need to focus their energies and efforts on human capital. They need to revalitze the human capital of the region, strenthening skills and empowering people. Central Americans deserve to live better, with greater skills, education and opportunities, and with access to political power that does not resort to clientelism and corruption.