Over the past few years, Mexicans have sent money back home to their families, friends, and others. Between 2017 to 2022, remittances sent to Mexico from the US have experienced double-digit growth, and during pandemic times (2020-2022) they nearly doubled in absolute numbers to 41 percent. In 2022, remittance volume reached a 20 year high at nearly US$59 billion. In 2023, over US$63 billion was remitted representing a growth rate of eight percent year over year (YoY). While remittance growth rates are showing signs of deceleration, volume is estimated to reach over US$65 billion by the end of 2024.

In the current context, remittance volume will continue and play a central role in US-Mexico relations. As was the case in 2023, remittance growth this year can be attributed to simultaneous increases in migration to the US, transfer frequency, number of senders, and the annual principal amount. Based on available data and current trends, remittance volume will grow by approximately three percent in 2024. This growth rate is lower than rates forecasted for the top 10 recipient countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

The following briefing offers an update on remittance growth in Mexico for 2024 by looking at past trends as well as key issues. Additionally, the memo shows how government policy has sought to intervene at the point of sending or receiving in certain ways, and that the overall upward trend is sustained by migration and remittance frequency. Lastly, the memo signals a slowdown in principal sent that is partly associated with microeconomic inflationary trends.

FIGURE 1: FAMILY REMITTANCES TO MEXICO, 2001-2024

Source: Banco de México

Remittances: A Contextual Analysis by Country

Mexico

Remittances have been a focus of attention of several presidents and leaders in Mexico since its democratic transition. During his administration, President Vicente Fox referred to Mexican migrants as the VIP (Very Important Paisanos). Under President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) there has been a shift in thinking since 2016. AMLO had first lamented Mexico’s reliance on remittances, then applauded the increased volumes sent, specifically during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has since recognized the significant role remittances play in “reactivating” the Mexican economy. AMLO has made remittances a part of his economic strategy in the past few years and has thanked migrants’ role in supporting their families back home. Over the course of his administration, remittances as a percent of Mexico’s gross domestic product have increased from 2.8 percent in 2019 to 4.2 percent in 2023.

FIGURE 2: REMITTANCES TO MEXICO, 2001-2023

Source: Banco de México and Word Bank Data

FIGURE 3: MEXICO’S GDP AND GDP PER CAPITA GROWTH (%), 2001-2023

Source: Word Bank Data

Similarly, public policies on remittances have been on the radar of different governments, from the creation in the early 2000s of the Banco del Ahorro Nacional y Servicios Financieros (Bansefi) and the Red de la Gente program, to its reincarnation under the AMLO administration – “Financiera para el Bienestar” (FINABIEN) – which includes a remittance service transfer product on a debit card that aims to provide greater access to remittances at a lower cost – particularly in rural areas. The debit card has processed 25,000 transfers, moving US$10 million, and has distributed cards to more than 76,000 holders in the US, and 205,000 in Mexico. A drop in the bucket when compared to the total transfers to Mexico in 2023, President-Elect Claudia Sheinbaum has promised to continue and expand FINABIEN, encourage greater financial inclusion, and regularize and protect migrant workers residing in the US. Yet, Mexican migrants still largely trust the prevailing remittance intermediation market when selecting a sending method.

United States

In the United States, policy discussions surrounding remittances have occurred within the context of various debates, whether it is immigration issues or illicit fund transfers. More recently, it has taken place against the backdrop of a polarizing national discussion on immigration. In this environment, some politicians have sought to introduce blanket fees and taxes on remittance flows – a percentage of which, they claim, is directed toward the finances of transnational criminal organizations (TCOs). In 2009, Oklahoma’s HB 2250, quickly became the legislative mold for state and national legislatures seeking to implement similar measures. The bill introduced a flat fee for all remittances under US$500 alongside a one percent fee for amounts greater than US$500. While this bill became law, similar measures have found little to no traction in other states. Yet, as can be seen in Table 1, proposals have attempted to introduce increasingly higher flat taxes on remittances – reaching 10 percent in recent years.

At the national level, in 2016, President Trump floated the idea that remittance flows to Mexico could be withheld and used to fund his plan for a border wall. During his administration, the idea quickly fizzled out despite the introduction of the Border Wall Funding Act of 2017 which called for a two percent remittance tax. The idea of employing a remittance tax to fund the wall remained dormant until Governor Ron DeSantis (R-FL) revived the idea during his 2024 presidential bid. Since then, there have been several proposals initiated at the state level and one at the national level. In December 2023, Rep. Hern (R-OK) with Sen. JD Vance (R-OH) – currently Pres. Trump’s 2024 running mate – introduced the Withholding Illegal Revenue Entering Drug Markets (WIRED) Act in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The bill seeks to introduce a 10 percent flat tax for remittances nationwide.

According to data from the Central Bank of Mexico, over 96 percent of remittances entering Mexico come from the US. With remittance dependence relatively high when compared to the past two decades, any tax placed on remittances will negatively affect the Mexican economy in an outsized manner.

TABLE 1: REMITTANCE FEE/TAX PROPOSALS IN THE US, 2009-2024

|

Legislature |

Year |

Bill |

Fee |

Revenue Destination |

Result of Proposal |

|

Oklahoma |

2009 |

HB 2250 |

US$5.00 for transfers under US$500.00, 1% fee thereafter |

Drug Money Laundering and Wire Transmitter Revolving Fund |

Became law: 63 § 2-503.1j |

|

Georgia |

2017 |

HB 66 |

US10.00 fee for transfers under US$500.00, 2% fee thereafter |

State Treasury |

Second Readers (Dead) |

|

Iowa |

2017 |

HSB 150 |

1% fee for all transfers |

Financial Crime and Wire Transmitter Fund |

House Judiciary Committee Recommends Passage (Dead) |

|

United States |

2017 |

HR 1813 |

2% fee for all transfers |

US-Mexico Border Wall |

Referred to the Committee on the Judiciary – Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, Homeland Security, and Investigations (Dead) |

|

Nebraska |

2018 |

LB 1016 |

US$5.00 fee if under $166.66, 3% fee thereafter |

Property Tax Credit Cash Fund |

Heard in Revenue Committee (Dead) |

|

Pennsylvania |

2022 |

SB 1158 |

2% fee for all transfers (not to exceed US$5,000.00) |

Property Tax Relief Fund |

Referred to Banking and Insurance Committee (Dead) |

|

Florida (Grand Jury Proposal) |

2023 |

SC 22-796 |

US$5.00 fee if under US$500.00, 1% fee thereafter |

“Agency or fund as the legislature may deem appropriate” |

|

|

Texas |

2023 |

HB 4743 |

10% fee for all transfers |

General Revenue |

Referred to Ways and Means Committee |

|

United States |

2023 |

HR 6817 | S 3516 |

10% fee for all transfers |

Border Enforcement Trust Fund |

Referred to House Committee on Homeland Security – Subcommittee on Border Security and Enforcement/Referred to Senate Committee on Finance |

|

Ohio |

2024 |

HB 451 |

7% fee for all transfers |

Withholding Illegal Revenue Entering Drug Markets Fund |

Referred to Ways and Means Committee |

|

Pennsylvania |

2024 |

SB 1170 |

10% fee for all transfers |

Property Tax Relief Fund |

Referred to Senate Banking and Insurance Committee |

|

Arizona |

2024 |

HCR 2045 |

30% fee for all transfers from persons unlawfully in US to outside of the US |

Department of Public Safety; Department of Emergency and Military Affairs; Arizona Department of Homeland Security (one-third of revenues each) |

Second Readers (Dead) |

Source: Bills accessed via corresponding State/National Legislature, “Result of Proposal” determined via State/National Legislature status

Meanwhile, since taking office, the Biden administration’s Treasury Department has increasingly engaged with Mexico’s Ministry of Finance and Public Credit on issues relating to money transfers within the context of concerns related to illicit fentanyl trade originating in China. Conversations[1] have centered on increasing information sharing on such items as investment screening, illicit finance tied to fentanyl, indicators of financial crime, and anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) efforts. As a result of these conversations, the two countries announced their intent to form a Bilateral Working Group on Foreign Investment Review. Although primarily intended to facilitate investment screening, both Secretary Janet Yellen and Minister Ramírez de la O have recognized that this forum presents an opportunity to discuss reducing the costs of remittances and have discussed improving payments system connectivity.

Migration Patterns from Mexico

Since 2019, increasing migration from Mexico to the US has been growing the pool of senders who are remitting. Over these past five years, the number of migrants from Mexico living in the US has grown 18 percent from 11.5 million to 13.6 million people. Increases have come in the form of both irregular entries and authorized migration – both of which have grown substantially since 2019.

Migration, both authorized and irregular, combine to expand the pool of senders. For example, last year, each category of migration (See Table 2) either met or surpassed pre-pandemic numbers. As a result, these increases have led to a nearly 34 percent increase in new remittance senders from 2019 to 2023.

Also expanding the pool of senders is an increased retention rate of Mexican migrants in the US. In 2010, the average time spent by Mexicans in the US was only 12 years. This grew to 19 years in 2019, 22 years in 2023, and is estimated to grow to 23 years in 2024. Evidence of this, the share of Mexicans who have spent more than 20 years in the US has grown from 30 percent in 2010 to an estimated 49 percent in 2024. Each year since 2018, two percent of migrants in the US stayed at least a year longer than the usual length of stay which has increased the lot of remittance senders by at least 20,000 people annually.

FIGURE 5: MEXICAN MIGRATION, 1997-2023

Source: Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

TABLE 2: MIGRATION FROM MEXICO TO THE UNITED STATES, 2010-2024

|

Year |

Irregular Migration |

Non-Immigrant Visas |

Legal Migration |

Total Migration |

Authorized Migration |

New Senders |

||

|

Border Apprehensions |

Irregular Entries |

BBBCC & BBBCV |

H2-A, H2-B |

|||||

|

2010 |

404,365 |

351,798 |

971,886 |

88,994 |

66,956 |

523,978 |

172,180 |

419,182 |

|

2015 |

267,885 |

233,060 |

1,166,668 |

156,369 |

82,323 |

491,235 |

258,175 |

392,988 |

|

2018 |

252,267 |

219,472 |

1,032,467 |

209,838 |

79,678 |

526,230 |

306,758 |

420,984 |

|

2019 |

252,403 |

334,906 |

1,106,852 |

222,694 |

54,780 |

630,864 |

295,958 |

504,691 |

|

2020 |

362,251 |

131,270 |

662,536 |

218,874 |

29,242 |

390,450 |

259,180 |

312,360 |

|

2021 |

725,008 |

91,828 |

512,889 |

73,479 |

40,784 |

214,656 |

122,828 |

171,725 |

|

2022 |

810,679 |

215,974 |

1,244,482 |

405,353 |

66,528 |

708,638 |

492,664 |

566,910 |

|

2023 |

756,521 |

370,581 |

1,926,292 |

371,327 |

68,582 |

842,659 |

472,078 |

674,127 |

Source: Author estimates, based off of DHS data.

Trends in Sender Behavior

Beyond an increased pool of senders in the United States, remittance volumes have also grown due to increased remittance frequencies and an increase in the annual principal. Since 2019, the total number of senders has grown from 8.9 million to over 10.2 million in 2023 – an increase of nearly 19 percent that has come largely from migration.

In addition to a greater number of senders, these senders are remitting more frequently than in previous years. Outpacing the growth in senders, the number of transactions has grown by over 23 percent. This suggests that senders are remitting more frequently. In prior decades, the average sender remitted between 12 and 14 times annually[2], in 2023 this has grown to over 15 times a year.

TABLE 3: SENDERS AND TRANSACTIONS OF MONEY TRANSFERRED TO MEXICO

|

Year |

Senders |

Transactions |

Share Sender/Transaction |

|

2019 |

8,617,263 |

9,503,118 |

0.9068 |

|

2020 |

8,910,101 |

10,345,888 |

0.8612 |

|

2021 |

9,071,093 |

10,431,756 |

0.8696 |

|

2022 |

9,602,571 |

11,042,956 |

0.8696 |

|

2023 |

10,234,565 |

11,769,750 |

0.8696 |

Source: Author estimates completed in July 2024.

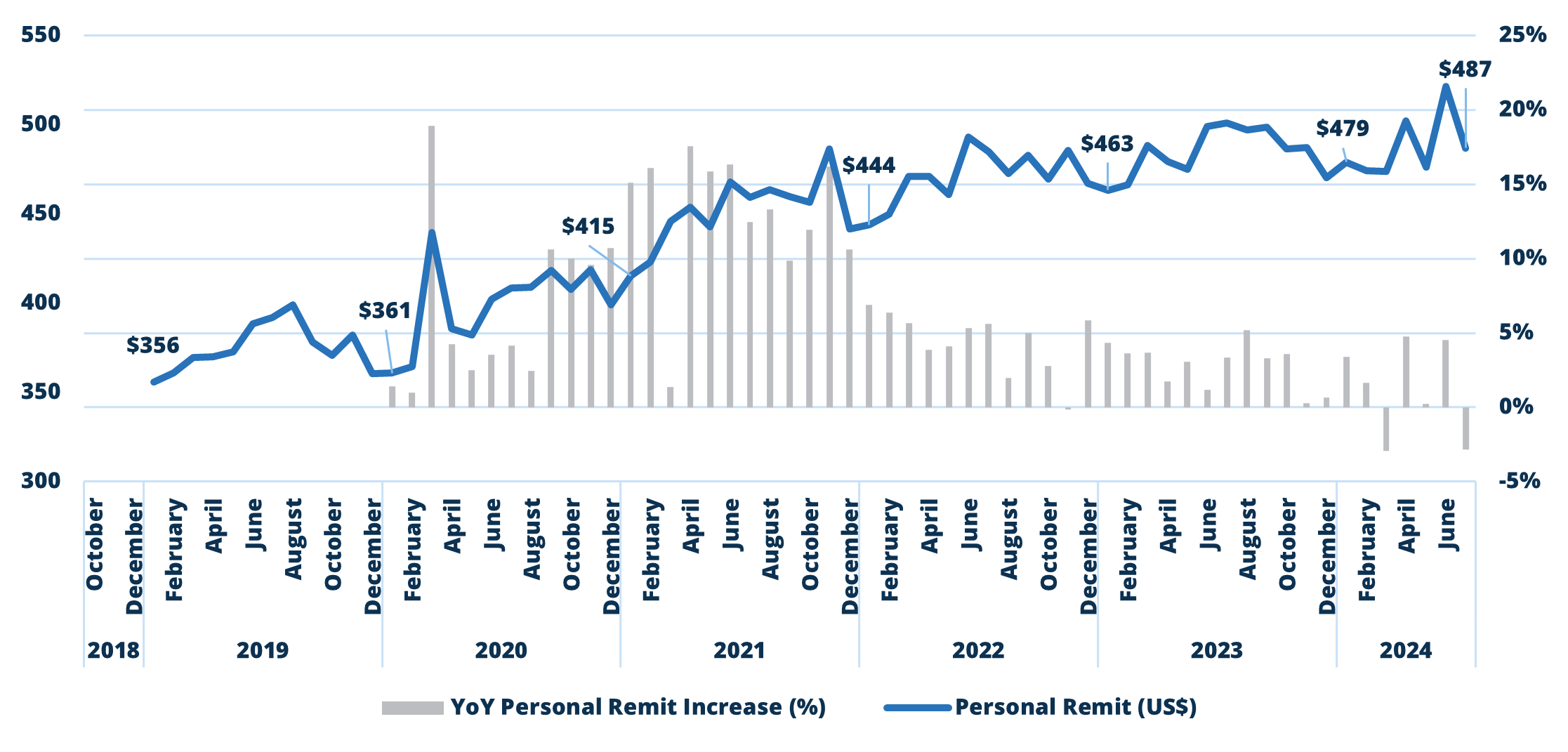

Moreover, Mexican migrants in the US are sending more on average per transaction. Over the past five years, the average principal sent has seen average monthly year-over-year increases of six percent. Most of these increases occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic (See Figure 6). Increases have since slowed in 2023 and the first half of 2024. The most recent average monthly principal sent (according to remittance company data) is US$487 per transaction.

When considering the overall increase in remittance volume sent to Mexico from the US, it is important to consider that this growth in principal has outpaced migration, specifically during the pandemic years. The change in principal has been more closely associated with US inflation rates than with Mexican inflation rates (See Figures 7 and 8).

FIGURE 6: AVERAGE PRINCIPAL SENT PER TRANSACTION (US$), 2019-2024

Source: Money transfer operator (MTO) proprietary data

FIGURE 7: US CONSUMER PRICE INDEX AND PRINCIPAL REMITTED, 2019-2024

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

FIGURE 8: MEXICAN CONSUMER PRICE INDEX AND PRINCIPAL REMITTED (US$), 2019-2024

Source: Inflation Portal, Banco de México

Remittance Estimates for 2024

This year will also see remittances continuing to reach new heights. The Migration, Remittances & Development Program estimates a maximum three percent increase in volume sent and that growth in new senders will continue to come from authorized as well as irregular migration, both of which are expected to increase in 2024. Despite signs pointing toward growth, YoY remittance growth rates have slowed since November 2021 and decreased for the first time this year (March) since April 2020. This confirms the Program’s assessment last year that remittances to Mexico will not continue to increase at rapid rates seen during the pandemic but will nonetheless steadily increase in 2024.

Growth, however, is unlikely to continue to come from principal sent as this has remained stable over the past two years. Therefore, continued growth in remittances will depend on steady inflows of migrants from Mexico, increased or steady payment frequencies by Mexican workers in the US, and increased or steady principal amounts sent home. Long-term, these factors will require continuous emigration from Mexico, constructive US-Mexico relations on issues related to migration and remittances, and macroeconomic health in the US.

TABLE 4: MIGRATION FROM MEXICO TO THE UNITED STATES, 2024 ESTIMATES

|

Migration Category |

2023 |

2024 Estimates |

|

Non-immigrant visas [H2A/H2B] |

371,327 |

425,000 |

|

Border apprehensions |

756,521 |

769,109 |

|

Irregular entries |

370,581 |

384,554 |

|

Legal migration |

68,582 |

72,011 |

|

New senders |

674,127 |

719,948 |

|

Median number of transactions |

11,769,750 |

12,545,944 |

|

Total number of senders |

10,234,565 |

10,909,517 |

|

Volume (US$) |

$63,278,727,631 |

$65,651,262,516 |

Source: Author estimates, based off data from DHS data and US Department of State immigration statistics.

FIGURE 9: MEXICAN REMITTANCES AND YOY GROWTH, 2018-2024

Source: Banco de México

Three Caveats

The estimates arrived upon in this piece should be considered alongside three other factors. First, seasonal migration is a revolving door and therefore some of those migrants will leave within two years. The annual net number of migrants is not calculated here.

Second, not all transactions are family to family transfers (P2P), nor do they all originate in the United States. Previous work suggests that one tenth of all transactions are business to business (B2B) or person to business (P2B) transfers.[3] Also, four percent of remittances to Mexico originate from countries other than the US.

Finally, it is also important to explore differences in principal and frequency remitted by agent based (or offline) transactions and internet based (or online or digital) transactions. Data from previous surveys suggest that migrants send 10 percent more when using digital transactions than when using agent-based transactions. These increases matter because digital based remittance transfers are over 40 percent of the originated flows and therefore may be influencing the flows as much as overall increases in the principal and migration.[4]

Endnotes

[1] Since June 2023, US-Mexico cooperation to prevent illicit finance has increased with key meetings taking place on: June 21, 2023; December 7, 2023; February 8/February 9, 2024; and April 16, 2024.

[2] Orozco, Manuel & Julia Yansura. 2017. On the Cusp of change. Migrant’s Use of the Internet for Remittance Transfer; Orozco, Manuel. 2021. A Commitment to Family: Remittances and the Covid-19 Pandemic.

[3] Orozco, Manuel. Workers Remittances. Lynne Reiner. 2013.

[4] Orozco, Manuel. Family Remittances Growth in 2021: Between Migration and Transaction Growth; 2022