This post is also available in: Español

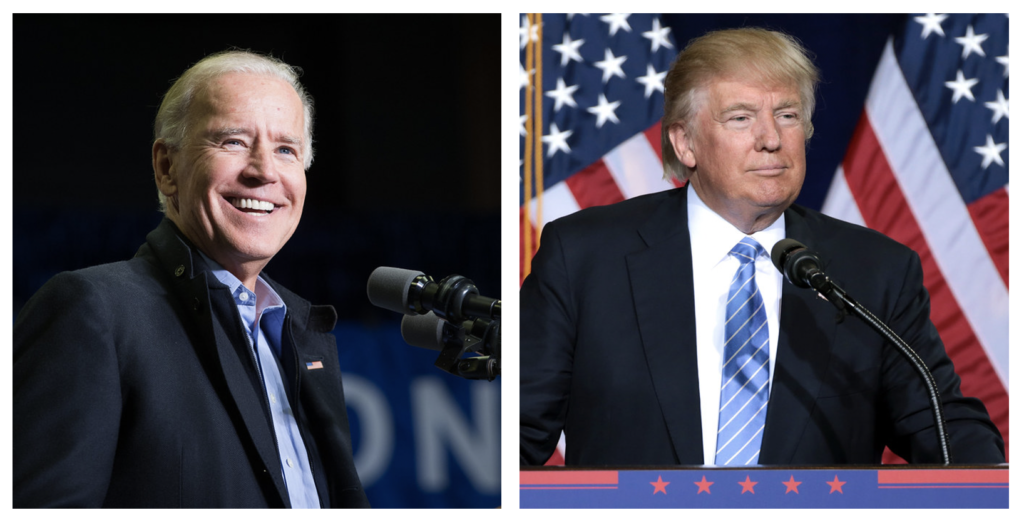

I lost count how many times over the past four years I heard US leaders doing their best to reassure the world, “this is not who we are.” “This” refers to the outrageous, norm-shattering behavior of President Donald Trump, that reached a low point of irresponsibility with his unfounded allegations of election fraud. Implicit in those words was that Trump’s win in 2016 was an aberration, an accident, and that the US would return to normal once the voters had another say at the polls. As it turns out, those US leaders were wrong.

This is who we are, or at least nearly half the country that voted for Trump in 2020. The country is perhaps more profoundly and bitterly polarized than ever, with a high level of mutual distrust. There are two separate realities, two sets of values. Trumpism proved not to be a fleeting phenomenon, but a movement that is likely to persist and be part of the US political landscape for some time. In this election, Trump showed that he controls the Republican Party, a party that reflects continuity on some issues but that has abandoned its traditionally pro-trade, pro-immigration positions. Reelected Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell, along with other Republican Senators, owe Trump a huge debt for their continued control of the Senate.

In some key respects, the election results were strikingly similar to those of 2016, when Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in an upset that shook the political world. Of course, there is one very significant difference. This time (as of this writing, on the afternoon of November 6) Trump seems likely to lose, and on January 20, 2021, Joe Biden is expected to become the 46th president of the United States. That said, the main reasons many believed that 2020 was different than 2016 had only modest effects — albeit apparently enough of an impact to decide the election.

First, Trump’s inept handling of the pandemic over the past 10 months failed to make as significant a dent in his support as expected. True, Biden won scattered pockets in rural areas, no doubt affected by the pandemic, that Trump had won four years ago, and that made the difference in regaining the “blue wall” in crucial rust belt states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. But what has to be regarded as the greatest defiance of political analysis and prognostication in recent memory, Trump did not appear to pay a substantial cost of nearly 240,000 dead, over 9 million cases, widespread business closings, and soaring joblessness. If it weren’t for the pandemic it seems likely that Trump would have been reelected. Indeed, it is easy to imagine several moves Trump might have made towards greater restraint and moderation that might have secured him another victory this time around.

Second, Joe Biden was not as polarizing a figure as Hillary Clinton. Biden enjoyed high favorability ratings and was perceived as decent, honorable, and empathetic, making him much harder to demonize (though the Trump campaign tried mightily). Still, despite the fact that Biden and Trump were polar opposites in terms of character and personality, Trump retained a substantial hold on the white working class and even made gains among African Americans and Latinos, especially males, compared to 2016. One might have expected a more significant support of Biden’s declared “battle for the soul of the nation.” One inescapable conclusion from the election is that, while Biden may have won the battle – defeating a populist incumbent is no mean feat — the war rages on.

And finally, 2020 was not 2016 because now Trump was an incumbent and not an insurgent attacking the establishment. Unlike four years ago, he had a record that could be assessed and criticized. But, remarkably, his 2020 campaign was a virtual replay of his 2016 campaign, with even less substance (e.g. little talk about “the wall” or terrible free trade deals) and very heavy on grievances, playing the victim, and sowing fear about what a Biden administration would do (Trump’s constant branding of Biden as a “socialist” helped him increase support among Cubans and Venezuelans in Miami Dade County and helped deliver Florida. Lesson: disinformation works). Analysts underestimated the depth of anger and resentment nearly half of Americans felt towards the “establishment,” even if Trump was the incumbent. Trump was still able to tap into those sentiments, much like Hugo Chavez did for many years in Venezuela, even when his government’s performance was dismal.

Going forward, the majority of the country that voted for Biden should understand that Trump’s durable support was the product of an array of factors. Many voted for Trump because they benefited from his economic policies pre-pandemic and backed his persistent calls to reopen the economy despite pandemic-related health risks. Others applauded his deregulation measures and conservative changes in the judiciary, including three new Supreme Court justices. To be sure, part of Trump’s constituency – most ominous for the country’s social peace and political stability – is comprised of racists, including white supremacists, whose violent actions the president has refused to criticize over the past four years. Still others were convinced that, despite Biden’s centrist credentials, his administration would be hijacked by leftist forces in the Democratic Party that they saw as ascendant and would ultimately result in intolerable tax increases and socialized medicine.

Biden will no doubt bring civility to the White House that has been missing over the past four years. Still, his task of governing will be daunting. Biden’s repeated calls for unity and his reassurance that he will be the president of all Americans — not just of those states who voted for him — strike the right note. But it is hard to know how much resonance those appeals will have in such a poisonous and polarized political environment. The record turnout and heightened civic engagement in the election offer some reasons to be hopeful.

It appears that Joe Biden, who has had his eye on the presidency since 1988, will finally get the top prize that has eluded him. In 2009, when he became vice president, Biden and president Barack Obama inherited a mess – a profound financial and economic crisis and two US-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But Biden’s 2020’s inheritance would dwarf that of 2009. Biden and his team will have to deal with an unsparing pandemic, a serious economic downturn, racial tensions, broken international alliances, and a government apparatus that has been substantially undermined, if not gutted entirely. The damage has been considerable by any measure. Without the goodwill and increased trust from a badly riven society, it is hard to see how that damage can be repaired. At the very least, it will take some time and require patience.

RELATED LINKS:

Shifter: “La estrategia de Trump de difundir que Biden es socialista fue muy exitosa”

Shifter: “Biden ganaría presidencia de Estados Unidos, pero el país está partido en dos”