In June 2019, after two decades of on and off negotiations, the European Union and Mercosur, the South American customs union consisting of Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay, reached an agreement to dramatically expand economic cooperation between the two blocs. This unprecedented free trade agreement would not only eliminate over 90 percent of tariffs on traded goods but would also open the door for more-extensive foreign direct investment and economic integration, as well as potentially bolster labor and environmental standards. Yet, over three years later, this agreement remains unratified. Mercosur was on the verge of finalizing its first major external free trade agreement since the bloc’s founding in 1991, but opposition from a group of EU member states placed the agreement back in limbo. Despite this setback, a change in Brazilian leadership and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have pushed the two blocs back to the negotiating table. With renewed optimism on both sides of the Atlantic following the election of Lula da Silva, a finalized free trade agreement (FTA) once again looks to be within reach and could even be ratified by July of this year. However, a handful of disagreements remain, and the way in which negotiators from both blocs address these points of friction will determine whether an agreement is finally reached, as well as who the greatest beneficiaries of such a deal would be.

Despite finally reaching an agreement in 2019, it immediately became clear that ratification of the FTA would be unlikely, driven by a combination of agricultural protectionism and environmental worries on the part of a handful of EU capitals. Ireland, France, and Austria were among the first countries to announce their opposition to the FTA, and about half a dozen other EU capitals followed suit in promising not to ratify the 2019 version of the agreement. European farmers, especially in France, staunchly opposed the agreement, citing their inability to compete with South American agribusiness, especially in the areas of meat, sugar, and ethanol production.

Under normal circumstances, such naked protectionism would have had a harder time generating the political capital needed to completely paralyze the ratification process. However, given then-Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s implicit endorsement of Amazon deforestation and reckless disregard for the environment, it became difficult to disentangle legitimate environmentalist critiques from protectionist impulses. Environmental critics, such as the European Greens, proclaimed that a free trade deal with Mercosur was incompatible with the EU’s climate goals, contending that it would not only endorse Bolsonaro’s destructive behavior, but may also lead to greater deforestation and environmental degradation as a result of an expansion in Mercosur’s agricultural and mining sectors. As Detlef Nolte of the German Council on Foreign Relations argues, Bolsonaro’s election was a “stroke of luck” for trade protectionists, as his anti-environmental antics “enabled agricultural lobbyists to hide their protectionist objectives behind an environmental mask.” Though Brazilian officials lambasted these countries’ environmental concerns as thinly veiled protectionism, these objections made the FTA politically untenable in Europe under a Bolsonaro presidency.

Though progress toward ratifying the agreement remained stagnant up until 2022, the events of the past year have made a finalized EU-Mercosur agreement a tangible possibility once again. No factor has played a greater role in this than Brazil’s recent change in leadership, with progress towards a new agreement picking up steam since leftist president Lula da Silva returned to office in January. In stark contrast with his predecessor, Lula has gone to great lengths to assure the world of his commitment to curbing deforestation and combatting climate change. On his first day in office, he signed seven environment-focused executive orders, including one reactivating the country’s Amazon Fund, a mechanism aimed at funneling global capital into rainforest protection with assets exceeding US$1 billion.

Moreover, Lula’s Partido Trabalhadores (PT) administration has not only signaled that it is willing to work with the EU to finalize an agreement but has made the trade deal a primary issue of concern. Lula has expressed his support for the deal, stating that it is “urgent” that Mercosur finalize its FTA with the EU before advancing other trade deals. He has also spoken in favor of making changes to the agreement passed in 2019, specifically in the area of government procurement. Additionally, Minister of Environment Marina Silva, an esteemed activist from the Amazonian state of Acre, has stated that her top priority will be “fixing issues” preventing the FTA from being ratified.

Though it is unlikely that any progress would have been made under a second Bolsonaro term, the EU announced its intent to return to the negotiating table even before Brazil’s presidential election, in large part due to the fallout from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The painful swell in commodities prices, and especially in the cost of natural gas, caused European leadership to recognize the dangers of a non-diversified supply chain and economic dependence on authoritarian powers. Much of the EU’s recent effort to push through a plethora of trade deals, not only with Mercosur, but with Mexico, Chile, and others, has been driven by the recognition that its national security is best served by reducing its reliance on “single suppliers.”

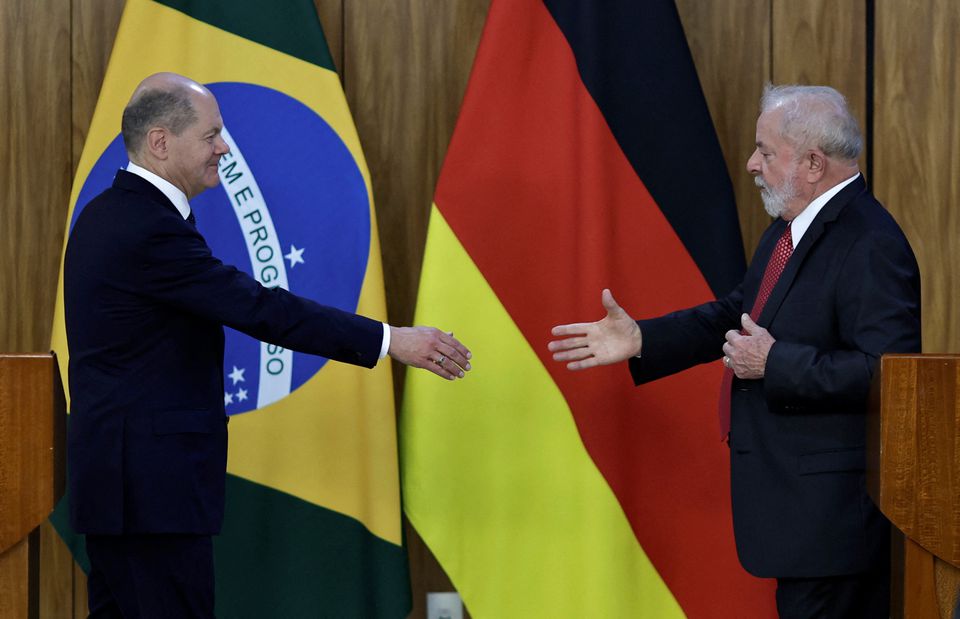

As a result of these developments, optimism for a finalized FTA has grown significantly on both sides of the Atlantic over the past year and only accelerated through the first months of 2023. Chancellor of Germany Olaf Scholz’s recent tour of South America included stops in both Brasilia and Buenos Aires with the EU-Mercosur deal at the top of the agenda. Plus, a growing number of European countries, including Greece and Spain, have thrown their weight behind the negotiations, with one Spanish Member of European Parliament (MEP) calling the present moment a “window of opportunity.” With this newfound support for the deal, European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans has announced that the EU hopes to ratify the agreement prior to the bloc’s next Latin America summit in July.

Despite these high hopes, the deal has failed to garner universal support and still faces opposition from a variety of critics. The largest barrier to a finalized FTA is the European capital that has most frustrated negotiations over the past two decades: Paris. France’s junior trade minister, Olivier Becht, has stated that,

“On Mercosur, our position hasn’t changed. It’s not Lula’s election that suddenly makes the Mercosur [deal] acceptable.”

– Olivier Becht, Minister of Foreign Trade, France

French MEP Marie-Pierre Vedrenne has called for binding environmental provisions before any FTA is ratified. Though Paris has mainly voiced concern over environmental issues, there is little doubt that agricultural protectionism has driven most of France’s opposition to the agreement, especially since Lula took office.

While French protectionism is the largest hurdle left to clear, it is hardly the only one. In Europe, France is not the only country calling for binding environmental provisions and such a measure may be necessary to satisfy European environmentalists. On the other side of the Atlantic, there are hangups as well. Most importantly, binding environmental protections have proven to be a non-starter for the PT administration up to this point, plus it may be impossible to pass such provisions through a more conservative Brazilian congress. Additionally, Brazil and Argentina are still interested in modifying the existing agreement to carve out limited protections for their manufacturing sectors and adjust the limitations on government procurement, which could complicate negotiations. Lastly, for all the support that the EU-Mercosur deal has garnered among Mercosur’s elected officials, many of the bloc’s civil society organizations have expressed unease about the effects of the trade deal. In February, members of the Brazilian Front Against the Mercosur-EU FTA, representing over 200 Brazilian NGOs, convened in Brasilia to meet with government deputies from both EU and Mercosur countries to voice their worries regarding the agreement. The front presented 10 primary concerns, among them that the FTA would benefit international capital at the expense of small and medium-size Brazilian businesses and could also cause further environmental degradation.

Ratifying the EU-Mercosur trade deal by the July target date will require a combination of compromise and creativity. The success of the upcoming negotiations will largely hinge on Brussels’ and Brasilia’s ability to secure French support for the agreement. Brazil and Argentina will likely have to assuage the French agricultural sector’s concerns, for example by accepting smaller quota expansions for some key products and perhaps even ceding ground on protections for their own manufacturing industries to propel the deal past the finish line. Foreseeing the potential for deadlock, the European Commission has floated the possibility of a “split” deal, dividing the agreement into two parts. The Council of the EU and European Parliament could pass a central agreement covering solely trade issues, while an expanded agreement containing the non-trade provisions of the deal would require approval from all EU member governments and would be ratified later if it eventually receives universal support. However, several EU members, including France, have voiced their dissatisfaction with this proposal, asking for the FTA to be presented as a “mixed” agreement, tying the two pieces together in a single arrangement.

Even though much of the FTA’s potential lies outside of the standard commercial gains from free trade, a split deal may be acceptable to Brussels. European manufacturers would profit from greater access to the Brazilian and Argentine markets and European consumers would benefit from cheaper commodities and food, but the FTA is most alluring to the EU because of its strategic and geopolitical implications. Josep Borrell, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, has argued that,

“The EU-Mercosur agreement is much more than a trade deal. It is a deeply political instrument that, by advancing dialogue and cooperation, would seal a strategic alliance between two regions that are among the world’s most closely aligned in terms of interests and values, sharing a similar vision of the kind of societies we want.”

– Josep Borrell, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy

Though Borrell is correct in his assessment of the agreement’s potential, the EU’s primary strategic goal of securing its commodities supply chains would be accomplished even with a split deal. While the FTA would decrease European dependence on Russia and China, it is doubtful that even a mixed deal would meaningfully reduce the Mercosur bloc’s dependence on these same illiberal states for their own development, at least in the short term.

While a split deal may be enough for the EU, it would amount to a hollow victory for Mercosur. This is not to say that the commercial benefits of a bare bones FTA with the EU would be insignificant. Consumer prices would drop throughout the bloc, likely by 1.5-2.1 percent in Brazil according to an estimate by the London School of Economics. Plus, the increase in commodities exports would provide a much-needed boost to the Brazilian and Argentine economies. However, the most beneficial aspects of the trade deal for Mercosur lie in its provisions on investment and intellectual property, which could pave the road for structural economic transformation in the South American bloc.

While there is a consensus among Brazilian economists that the country’s long-term development will require a reduction in reliance on commodities exports, there is still significant disagreement regarding the potential effects of the EU-Mercosur FTA. Some economists, such as Edmar Bacha, one of the architects of the Plano Cruzeiro and Plano Real, contend that the FTA is vital for inserting Brazil into the global economic order of the 21st century. Similarly, Fernando Vieira of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro asserts that,

“In order to transition away from commodity-centered economic models, and their associated vulnerabilities, the Mercosur countries are increasingly seeking to reform their regulatory spheres, absorb new technologies, and attract new foreign investment; the free trade agreement with the EU constitutes a major step in this direction.”

– Fernando Vieira, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro

Yet, others, such as the University of São Paulo’s Laura Carvalho, claim that the agreement will accelerate deindustrialization and decimate Brazil’s high-value-added manufacturing sector, damaging the country’s economy in the long run. In any case, if a split deal is passed, it is unlikely that the accompanying provisions on technology transfer and investment would be ratified any time soon, so it is vital that Mercosur secures a mixed deal if it hopes to fully benefit from this agreement.

Between the back-to-back Swedish and Spanish presidencies of the EU in 2023, the election of Lula da Silva, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the conditions for a finalized FTA between the two blocs are as optimal as they have ever been. Yet, multiple barriers to a finalized agreement remain, chief among them French opposition. The premise of a split deal may be tantalizing to beleaguered officials desperate to finalize an agreement more than two decades in the making. Yet, this move would result in a deal that fails to meet some of the two blocs’ most important objectives and would be especially disappointing for Mercosur. The clock is ticking for representatives to compromise on an agreement that is acceptable to all actors involved, as it seems unlikely that policymakers will be willing to continue dedicating time and effort to a dialogue that has continually failed to bear fruit, even under the most favorable of circumstances. Plus, with Uruguay shifting its attention to the Pacific, failure to deliver once again could even spell the beginning of the end for Mercosur. However, if the EU and Mercosur manage to reach a settlement on a mixed deal, it could mark the beginning of a much deeper trans-Atlantic partnership and a new era in Mercosur’s engagement with the rest of the world.