The United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) said in a report published on Nov. 12 that poverty levels in Latin America fell last year to a 33-year low, Reuters reported. The report also said that the region still suffers from high inequality, limited social mobility and weak social cohesion, despite declining poverty rates. What are the reasons for Latin America’s improvement in reducing poverty, and which countries are leading the way? Which countries are still lagging behind? What are the steps leaders need to take to reduce income inequality in the long term?

Nora Lustig, professor of Latin American economics at Tulane University and nonresident senior fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue: “The optimistic tone of the headline announcing that poverty levels in Latin America fell last year to a 33-year low is a bit misleading. According to the same ECLAC report, the decline in the region’s poverty and extreme poverty rates is primarily due to Brazil, ‘as the number of people lifted out of poverty in that country was equivalent to 80 percent of the change in the indicator at the Latin American level.’ In fact, of the 12 countries included in the ECLAC report, extreme poverty declined in only three (Brazil, Paraguay and Colombia). In the remaining nine countries, extreme poverty slightly increased or remained practically the same. Thus, most of the region is still lagging behind in eradicating extreme poverty. Even under optimistic scenarios, Latin America is unlikely to reach the U.N. Sustainable Development Goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030. Moreover, in about half of the countries in the region, fiscal policy increases poverty. That is, a portion of the poor pay more in taxes than they receive in transfers. This startling result is primarily the consequence of high consumption taxes on basic goods and/or that transfers to the poor are too low and/or have insufficient coverage. Given that growth remains elusive, fiscal redistribution may have to play a more prominent role in extreme poverty eradication and inequality reduction. Although noncontributory transfer programs have become quite widespread in the region, there are two key factors that limit their effect on poverty and inequality: the small size of the transfers and their sizable undercoverage of the poor. On the tax side, the region’s systems tend to have a low redistributive impact. Among the salient factors, this is because countries collect relatively little personal income and property taxes, which are often highly progressive taxes. In addition, while income taxes are progressive, their progressively could be higher. For instance, the top marginal income tax rate in Latin America is 30 percent while it is over 45 percent in advanced OECD countries.”

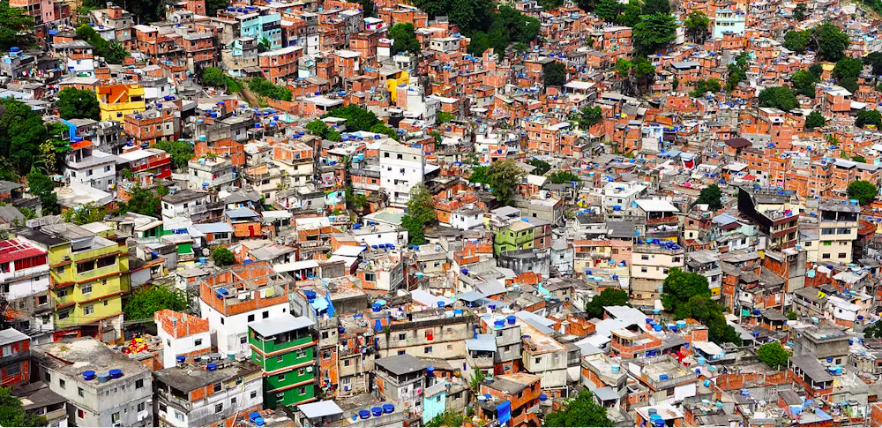

Pedro Francke, former Peruvian finance minister: “In Latin America, poverty in 2023 was 27.3 percent, almost the same level as 2014 (27.7 percent), but extreme poverty was 2.7 points higher than a decade before. Compared to a decade earlier, between 2002 and 2010, when poverty was reduced by 1.5 percentage points per year, subsequent results have been disappointing; the Covid-19 pandemic brought an economic crisis, impoverished the region that was already going downhill in the previous five-year period, between 2014 and 2019 and worsened inequality. After that, the recovery has not been rapid; economic and social progress has been slow. The main cause is very low growth, which was just 0.9 percent annually between 2015-2024. As the ECLAC report indicates, a ‘major productive transformation based on the scale and improvement of productive development policies’ is essential to confront the trap of low growth and high inequality, since the region does not seem to be taking advantage of the recovery of global growth and technological advances, as well as the opportunities that a new time of trade conflict between the United States and China opens up. Along with this, fiscal reforms are necessary to make the systems more progressive and progress toward social protection systems with greater coverage and effectiveness. A fundamental issue is the need to strengthen democracy and state capacities, since weak governance is generating greater problems of citizen insecurity and political instability in the region that aggravate the situation.”

Carlos Rodríguez-Castelán, practice manager in poverty and equity for Latin American and the Caribbean at the World Bank: “The recent poverty reduction in Latin America has been driven by stronger labor markets and, to a lesser extent, public transfers. According to the World Bank’s latest Regional Poverty and Inequality Update, between 2021 and 2023, poverty fell by almost five percentage points from 29.7 to 25 percent. Increased employment rates and higher labor earnings contributed to a 1.8 and a 1.5 percentage point reduction in poverty, respectively. Public transfers have contributed to a 1.1 percentage point decline, but in the coming years, fiscal pressures may reduce the effectiveness of this policy instrument. Leading the way in poverty reduction are Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and the Dominican Republic, where labor markets have been crucial. However, job quality remains a concern. To achieve longterm poverty reduction, leaders must focus on implementing labor market reforms that promote job creation, fair wages, job security and decent working conditions. Also, they should focus on investing in education to equip the work force with the skills required in today’s economy, enhancing digital infrastructure and encouraging both workers and employers to embrace new technologies.”

Maria Velez de Berliner, chief strategy officer at RTG-Red Team Group Inc.: “Government policy and money laundering lie behind the decrease in poverty. The decrease is skewed by poverty in Argentina due to the current economic shock, and in Haiti due to insecurity. Latin America has 292 million paid jobs; one fifth of these are in the informal sector because it is next to impossible to get a job after 45, and those between 18 and 35 find it very difficult, sometimes impossible, to find a legal job due to poor education or lack of employment opportunities. This means growth must occur in the informal or money laundering sectors since people must make a living one way or another. Regional growth for 2024 could be as low as 1.5 percent, which augurs an increase in poverty and inequality in the formal sectors. And innovation, the engine of 21st century growth, is stunted due to lack of, or poor, primary and secondary education or lack of corporate incentives. Therefore, governments must, first, make primary and secondary education move from learning by rote to experiential learning and improve the deficient teaching pool. Second, they must relax company creation, management and tax structures so companies can grow and enlarge their employment rolls. Third, they must reward entrepreneurship and incentivize innovation as a path to work-related upper mobility. These are the only operative ways in which the poverty and inequality that characterizes the region could be tackled. Otherwise, we will see increasing tradebased money laundering in Colombia, Brazil, Panama and Venezuela.”

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.

The Latin America Advisor features Q&A from leaders in politics, economics, and finance every business day. It is available to members of the Dialogue’s Corporate Program and others by subscription.